Benevolent Psyops for a Network State

Plus: How to form a movement with a heart and a gut and not just a brain.

Those who arrive at Thekla can see little of the city, beyond the plank fences, the sackcloth screens, the scaffoldings, the metal armatures, the wooden catwalks hanging from ropes or supported by sawhorses, the ladders, the trestles. If you ask, “Why is Thekla’s construction taking such a long time?” the inhabitants continue hoisting sacks, lowering leaded strings, moving long brushes up and down, as they answer, “So that its destruction cannot begin.”

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

The network state movement is aspy. That is neither an insult nor an accusation. Some of my best friends are neurodivergent, and the world’s greatest innovations come from the Gray Tribe's most talented nerds. Still, most early network-state faithful are infatuated with realizing the concept itself. Das ding in sich.

The desire to build a network state is insufficient because a network state simpliciter is mostly content-free. It has no soul. And the movement will have to attract more than coders and crypto bros. Coders and crypto bros can serve as the executive nerve center—the head—but the movement needs a beating heart and a firey gut.

It will also need an animating force that aligns head, heart, and gut such that it’s capable of attracting Renaissance Men and Women.

For the uninitiated: The network state is an emerging concept/movement in the domain of socio-political organization, blending traditional notions of statehood with the potential of digital networks. Envisioned as a decentralized, community-driven entity, a network state transcends physical boundaries, leveraging technology to unite people across the globe around shared values. As network states evolve, they’ll challenge conventional ideas about citizenship, governance, and community, suggesting a future where digital and physical realities are more integrated in certain respects but more separated in others. But such abstraction is a ghost that needs a body to inhabit.

The Moral Kernal

With gray in my temples, I remember when a couple of smart UT students, Michael Goldstein and Daniel Krawisz, told me about a technology that would change my life forever. The year was 2011. The technology was Bitcoin.

Americans were still reeling from the financial crisis of 2008-09, and there was something electric in the air. I was already against the grotesque bailouts and wanted to “end the Fed.” I immediately got the implications of the tech, but what caught fire in me was a deeper set of commitments. These two computer science kids channeled something moral and deeply doctrinal in Bitcoin. Bitcoin had more of a sense of mission at that time—a moral kernel—than it does today. And Bitcoin was exodology made manifest, a retelling of the escape-from-Pharaoh story.

A couple of years went by.

I was Editor at the nation’s oldest organization dedicated to freedom and free markets. I published one of the most important pieces I would publish during my tenure there. In that piece, Jeffrey Tucker wrote:

What is ideological brutalism? It strips down the theory to its rawest and most fundamental parts and pushes the application of those parts to the foreground. It tests the limits of the idea by tossing out the finesse, the refinements, the grace, the decency, the accoutrements. It cares nothing for the larger cause of civility and the beauty of results. It is only interested in the pure functionality of the parts. It dares anyone to question the overall look and feel of the ideological apparatus, and shouts down people who do so as being insufficiently devoted to the core of the theory, which itself is asserted without context or regard for aesthetics.

A lot of people threw tomatoes at Tucker for that piece.

Jeffrey Tucker can come across as an eccentric, a dandy, and a poseur, but there are undeniable flashes of genius in his writing. “Against Libertarian Brutalism” was no exception. This had been a vitally important critique for the target audience to consider, which is why so many tried to stone him as an apostate. No wonder so many have since abandoned liberalism to join the cult of populism or the cult of woke.

There might have been a hundred reasons to throw things at Jeffrey Tucker. But this wasn’t one of them.

The One Commandment

If it is to succeed, The Network State movement cannot be a brutalist movement, either. And Balaji Srinivasan, who wrote the network state instruction manual, cannot be its only avatar. I’ll explore why in a moment.

But first, remember Srinivasan’s One Commandment:

Every new startup society needs to have a moral premise at its core, one that its founding nation subscribes to, one that is supported by a digital history that a more powerful state can’t delete107, one that justifies its existence as a righteous yet peaceful protest against the powers that be. (Emphases mine.)

As with Bitcoin, there are subtle ideological lessons in The Network State (the book), even more so than in the Bitcoin whitepaper, which manages to be laden with Satoshi’s values. All technological endeavors are value-laden, of course. But as with Bitcoin and Balaji, those working on catalyzing network states have to be more explicit, more aesthetic, and more evangelistic in relating a moral core. Or they must recruit the people who can and support them.

Srinivasan has never seemed comfortable as a prophet or pamphleteer and positions himself as a consultant and investor in his framework.

Even as there are subtler shades of morality and political theory in Srinivasan’s instruction manual, the movement risks lapsing into a tautological doom loop if it doesn’t find a moral core beyond We should totally build a network state.

And its prophet told us why: Any network state must justify its “existence as a righteous yet peaceful protest against the powers that be.” It must justify satyagraha.

It must justify underthrow.

The Founders’ Promise

New readers to Underthrow—the substack—might not yet know that we have a central organizing principle here—a moral core. Underthrow—the goal—is the peaceful but still powerful sibling of overthrow. Its means are the sum of peaceful human choices arrayed against unjust authority.

But the moral core was a promise made to everyone on earth:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

This had once been the moral core of the American project, and it can be that moral core again—but not just for Americans. The Founder’s project is and has always been a cosmopolitan project. And I can think of no movement more suitable to instantiate the governed’s consent than the network state in the twenty-first century. Sure as hell beats politics. Instead of lawyers making law as code, we now have coders making code as law. And these can work in interlocking tandem. But real communities of people—with love in their hearts and fire in their bellies—will have to run on that social operating system and its moral kernel.

But as I suggest, the movement needs more prophets or, at the very least, more pamphleteers.

Seven Steps to Network Statehood

Found a startup society. < We are here.

Organize it into a group capable of collective action.

Build trust offline and a cryptoeconomy online.

Crowdfund physical nodes.

Digitally connect physical communities.

Conduct an on-chain census.

Gain diplomatic recognition.

Prophets and Pamphleteers

Simon Sinek got famous for reminding you to know your why. I proposed that the “Consent of the Governed” should be our why. It worked to excite a bunch of yeomen with muskets to face down an imperial army. But if you have a more effective why than Jefferson & Co.’s thrusting middle and ring fingers aloft in the general direction of King George III, then by God, you must try your hand at being a prophet or a pamphleteer.

I’m doing my best in my little corner of the internet, but we need a syndicate. It looks like folks are trying to create one with the new ARC organization, but that looks more like a Who’s Who of Youtubers and Politicos than a real fraternal organization or a startup society.

We also need marketers and benevolent manipulators.

Benevolent Psyops

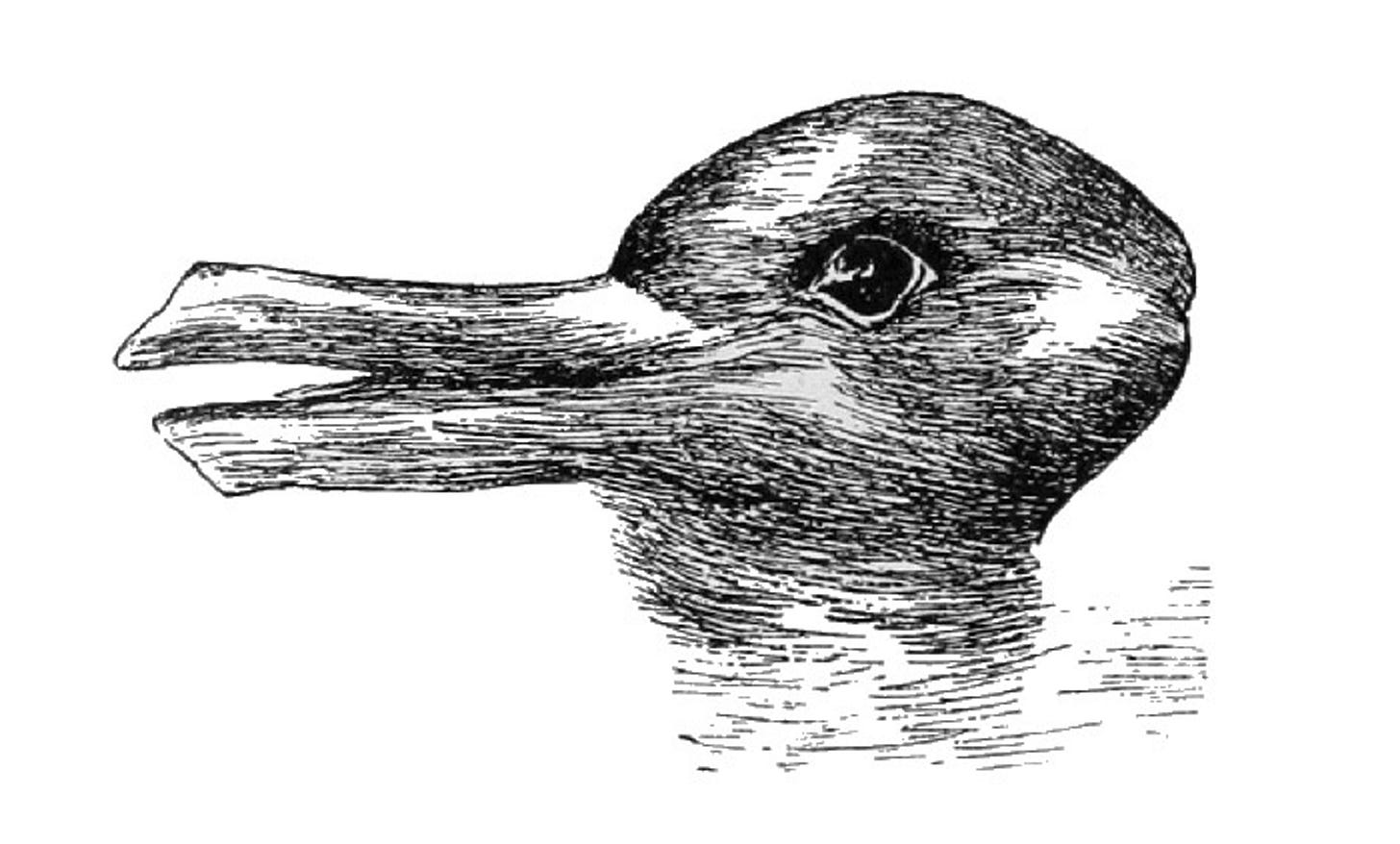

Ever heard of The Alchemist from Rory Sutherland? He employs some of the most wicked marketing arcana around. The man looks at the whole world like a Gestalt image or Necker Cube, picking out the hidden features while operating under the assumption that people can be motivated to do irrational things.

That is, he can not only see the duck and the rabbit, but he can also tell you who’s likely to order the duck or the rabbit from the menu and why. He senses our unconscious motivations and uses our irrationality against us. (Or is it for us?) He knows Rolls-Royces sell better at yacht or airplane shows than at car shows because if you’ve been looking at Learjets all afternoon, a $400,000 car is an impulse buy.

If I had a metric ton of cash, though, I wouldn’t buy a Rolls. I’d pay Rory Sutherland to work his wizardry, which is to say, to devise a startup society / fraternal society campaign. Not all movements can be marketed, but if anyone could do it, it’d be Sutherland.

Now, I should acknowledge that Bitcoin never had a marketing department. And I suppose if the creation of network states worked more like network marketing, my call to the prophets and pamphleteers would be unnecessary. I suspect, though, that Srinivasan’s One Commandment implies that the movement needs more evangelists.

As the world drowns in a $300 trillion sea of red ink, the US and EU are sino-forming themselves faster than you can say Great Leap Forward. It seems eminently rational to think people would want to abandon (not reform) the system we have right now, teetering as it is on civil conflict and economic collapse. But most people are either zombies or not paying attention.

So maybe, a la Rory Sutherland, we must persuade them to do something irrational.

Related:

On Forming the Jefferson Society

To attack the citadels built up on all sides against the human race by superstitions, despotisms, and prejudices, the Force must have a brain and a law. Then, its deeds of daring produce permanent results, and there is real progress. –Albert Pike Who are those men

“ those working on catalyzing network states have to be more explicit, more aesthetic, and more evangelistic in relating a moral core.”

As you know, I am intently focused on the moral/philosophical principles that justify our desire for network states and other new types of polities. Interestingly, though, I am sometimes admonished that moral/philosophical principles are precisely what people DON’T want. Most people, I am told, want something more ‘concrete.’

I do not believe this is true, at least not to the degree they say. But I still must acknowledge the fact that they say it.

Thoughts?

Beautiful.

America when it was founded had a code, a constitution, and Bill of Rights. It was one nation under God, which gave it a heart, per say.

If Network States are digital countries, as Balaji likes to say, then shouldn't they also have a code? One that is able to be changed, say, by the people? Maybe via a new system of sorts? One that could harness the wisdom of the entire Network?

Good stuff.

-Josh, SOPS