Democracy is Overrated

Another installment in the (perhaps neverending) Church of Politics series.

Democracy is also a form of worship.

It is the worship of Jackals by Jackasses.

—H. L. Mencken

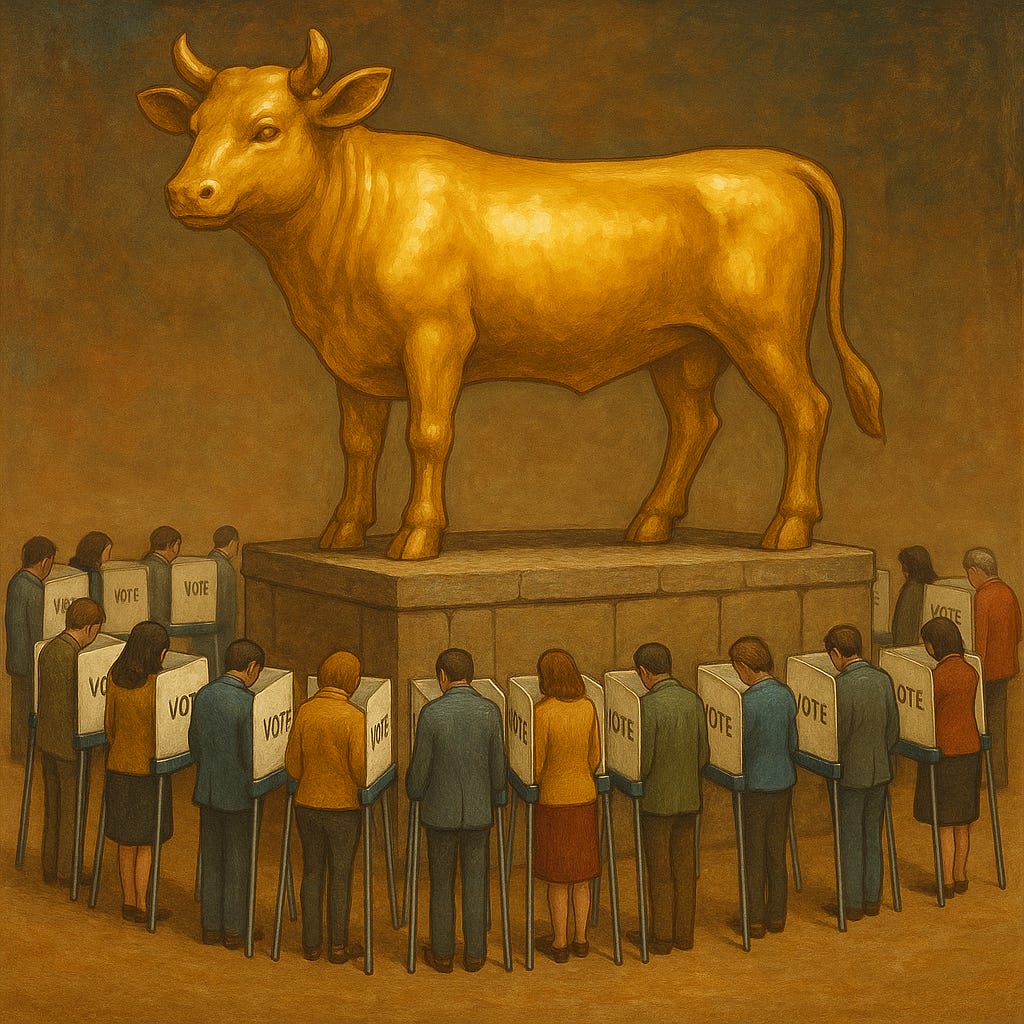

Another golden calf in the Church of Politics is faith in democracy. I know, I know. Voting is the only game in town. But if more of us scrutinized the system, many would realize just how much faith we place in this majority-rule business.

“Democracy is another way to allocate resources,” writes Carnegie Mellon economist Allen Meltzer.

Generally, those who succeed in the marketplace favor allocation by markets, not governments. Those who do not succeed favor government redistribution, joined by those who dislike capitalism or prefer collectively mandated ‘social justice’ over market efficiency. Actual social outcomes are a compromise between the two.

So what’s wrong with that compromise?

The renowned political economist Gordon Tullock argues that democracy is overrated.

“It’s said you’re more likely to get in a car crash on the way to the polling place,” Tullock says, “than to affect the outcome.”

Presumably, the point of voting is to change things you don't like or to make the world a better place by electing the ‘right’ people, but the likelihood that your vote will affect the outcome of an election is vanishingly small. And the ‘right’ people are almost always wrong.

Consider that it takes about 3,633,600 drops of water to fill a 40-gallon bathtub (90,840 drops per gallon). Considering that 155,240,953 people voted in the 2024 election, your vote is like a single drop in 43 bathtubs. What are the odds that your drop will fill the forty-third tub?

And yet democracy is the only game in town.

Now that constitutions no longer seem worth the parchment they’re scribbled on, suffrage has become the secular religion. It's as if we have a system that depends on getting a whole lot of people to do something irrational—at least from the standpoint of one person trying to effect change. It's a hive's rationality, perhaps. You have to be willing to spend your time and emotional energy for the "greater good." Just as the absence of a single worker ant won't make or break the construction of the mound, there is a point at which the colony would suffer without the contributions of many acting in concert. I guess that offers us some measure comfort as we go to the prayer booths polls.

So how might we better rationalize democracy?

Well, we could expand our definition of the voting "preference function" to include:

Getting all puffed up with a feeling of civic participation.

Getting an "I voted" sticker.

Getting to be involved, in some insignificant way, in the process of replacing a snake with a scoundrel.

Getting, in some sense, to "cheer for your team" or express yourself.

Knowing that your individual irrational behavior resulted in a positive outcome (provided your team a) wins and b) you don't become disillusioned soon after your team takes office).

Ain't democracy grand?

Despite all this, throngs will drag themselves to the polls next election. Honestly, I'm not sure I can explain why except to repeat: It’s the only game in town. For me, elections are like Christmastime to a Jew: find a way to enjoy the spectacle.

Voter Paradoxes

There are several voting paradoxes, but I’ll credit the Marquis de Condorcet and Kenneth Arrow for now. Irrational results can follow from majority-rule voting. For example, imagine you’re the owner of a small business. You need to decide on the business’s future, so you let your three top employees vote on three options:

Hire more employees and managers

Keep the status quo

Lay off employees and managers

The CFO prefers 1 > 2 > 3.

The HR manager prefers 2 > 3 > 1.

The production manager prefers 3 > 1 > 2.

When they vote between 1 and 2, option 1 wins (CFO + Production vs HR).

When they vote between 2 and 3, option 2 wins (CFO + HR vs Production).

But when they vote between 1 and 3, option 3 wins (HR + Production vs CFO).

So we have: 1 > 2, 2 > 3, but 3 > 1—a paradoxical cycle. Even though each individual’s preferences are rational, the group’s collective preference is not.

This same problem can arise in elections. Suppose three voters rank three candidates—Vance (R), Cuban (I), and Cortez (D)—as follows:

Voter 1: Vance > Cuban > Cortez

Voter 2: Cuban > Cortez > Vance

Voter 3: Cortez > Vance > Cuban

In head-to-head matchups: Vance beats Cuban, Cuban beats Cortez, and Cortez beats Vance. This circular outcome illustrates the Condorcet paradox: no candidate beats all others in pairwise contests, even though each voter has consistent preferences. In such cases, the “will of the majority” is incoherent, and election outcomes can fail to reflect stable majority preferences.

What about alternative voting systems?

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) can break cycles by eliminating the lowest-ranked candidate round by round, eventually yielding a single winner. However, the winner chosen may not be the “Condorcet winner” (the candidate who would beat all others head-to-head, if such a candidate exists). RCV avoids some paradoxes but introduces others, like situations where an individual ranking a candidate higher can actually cause them to lose.

Roy Minet proposes Approve/Approve/Disapprove Voting (AADV), which avoids some Condorcet cycles, but its design favors consensus candidates.

I have suggested taking a look at the Janáček Method, which appears to be vulnerable to strategic voting.

A more radical solution might be Cellular Democracy, which doesn’t resolve paradoxes directly, but mitigates their damage through decentralization.

Liquid democracy was a fashionable concept for a while.

It doesn’t matter what you think of these options. The duopoly has powerful incentives to see that the current election system remains in amber.

Clustering

But matters worsen for representative democracy. When you vote for a candidate, you’re not really voting for one thing but a cluster of things. It’s sort of like going to the supermarket and, instead of filling a shopping cart with the items you want, you have to choose from among three pre-filled shopping carts. You get to take that cart if you’re not outvoted; otherwise, you have to take a pre-filled cart based on others preferences.

And you’ll pay for it.

Making matters worse, by the time you get home with your choice of cart—the contents of which aren’t really what you wanted—you are probably going to get less of the things you chose at the store. This is because by the time you get home, the gremlins we’ll call “special interests” have already replaced many of the items you liked in your chosen basket with items they prefer. In other words, your preferences are further diminished by the preferences of those who have a far more direct stake in what’s in your cart than you do. They lobby to get what they want. So it’s not just that you can’t pick out your own groceries, it’s also that the cluster of groceries you thought you were getting is an illusion, because politicians almost always compromise away their promises.

Tyranny by the Many

Paradoxes and clustering aside, let’s suppose there is some magic about majority rule that manages more or less to capture people’s preferences. That leaves us with a deeper problem. Without sufficient checks on democracy, a majority can exploit a minority.

Non-vapers outnumber vapers in a municipality. The town holds a referendum and votes to limit vaping in private establishments such as bars and restaurants. What’s wrong with that? Bar and restaurant owners have property rights, which include the right to decide their own vaping policies. A restaurant or a bar is, after all, private property, not public property.

Less productive voters outnumber more productive voters. The former decides that more productive citizens should subsidize the less productive lifestyles of others. They raise taxes on the more-productive voters and redistribute the proceeds among themselves, which makes them even less productive over time. More productive voters have to be even more productive to maintain their lifestyle.

A majority of people with specific attributes decide, through majority rule, that they will be allowed to have rights over the time, labor, and property of people with different attributes.

In each case, don’t these minorities have rights?

We might refer to these examples as instances of “diffuse benefits, concentrated costs,” which inverts Olson’s formulation. Economist and economic historian Lawrence Reed reminds us that:

[T]hose democratic elements of our republic should be given their due. Elections are a political safety valve for dissident views, because ballots not bullets resolve disputes. But the saving grace of democracy is not that it ensures either good or limited government; it is nothing more than that the system allows for political change without violence—whether the change a majority favors is right or wrong, good or evil.

So, at least we can give the Golden Calf its due, even as we’re experiencing an uptick in political violence.

Tyranny by the Few

While the minority is getting screwed under representative democracy, the majority gets screwed, too—in different ways.

Political scientist Mancur Olson figured out the problem of concentrated benefits, diffuse costs—that is, small interest groups are nimble, vocal constituencies with direct interests in the outcome of this congressional bill or that (our grocery gremlins again). The rest of us stand to lose fractions on the dollar, kroner, or yen for any given bill’s provision, so we have comparatively less incentive to advocate vociferously for statutory change, much less pay attention to whether it’s being debated on the House or Senate floor.

The trouble is that all these diffuse costs add up over time in the form of higher prices, increased taxes, and general economic malaise. Most of what Congress doles out, after all, creates no economic value per dollar spent—except, of course, to special interests who almost always win.

"There is nothing sacrosanct about majority rule," economist Walter Williams said in an archived video conversation with James Buchanan. It can be a form of tyranny, after all, and the tyranny is compounded when moneyed interests are involved. When the state and business get into bed together, citizens lose. Democracy becomes but a shroud of sanctimony that obscures the loss of freedom and prosperity. And, of course, this state of affairs makes it more and more difficult to tell the difference between the rich parasites and real entrepreneurs.

Faith-based Initiatives

Faith in politicians and government bureaucrats is bad enough, but matters worsen when that faith supplants the trust bonds we have in one another.

Mencken puts it best:

What is any political campaign save a concerted effort to turn out a set of politicians who are admittedly bad and put in a set who are thought to be better? The former assumption, I believe is always sound; the latter is just as certainly false. For if experience teaches us anything at all it teaches us this: that a good politician, under democracy, is quite as unthinkable as an honest burglar.

It would seem that representative government is a system that both attracts and selects for sociopaths.

We also place too much faith in “the experts,” who serve as handmaidens for the sociopaths. Intellectuals in the media and academia act as a kind of priestly class for the church of politics. The university system has all the trappings of a cloister, and the media act as a fifth column.

We’ll leave that conversation for another day.

Let us not forget that the United States is not a democracy. It is a constitutional republic whose dysfunction may be ascribed in large part to a systematic setting aside of the blueprint.

We should roll the federal government back to 1820, return power to the states, and see what that does before quibbling about whether or not the model we were given works as intended.

"But the saving grace of democracy is not that it ensures either good or limited government; it is nothing more than that the system allows for political change without violence"

—I wonder if it would be quite as peaceful if more people understood what democracy actually is and how it is actually working…as opposed to the illusion we've been spoon-fed.