Fact, Fiction, and Falsehood

How to evaluate the information landscape and learn to employ the tools of Subversive Communication.

No more Noble Lies!

Throughout history, societies have leaned on myths and narratives that they "believed" to bind communities together or ignite a shared sense of purpose.

Then came the Enlightenment, flipping the script. It marked a shift from swallowing these stories as gospel to recognizing them as useful fictions—narratives that serve a purpose but aren’t etched in stone.

Humanity hit a major milestone: reason and empirical evidence started to edge out blind allegiance to tradition. It was Childhood’s End—the moment we grew up intellectually and gained the tools to critically examine our most sacred beliefs. —Jim Rutt

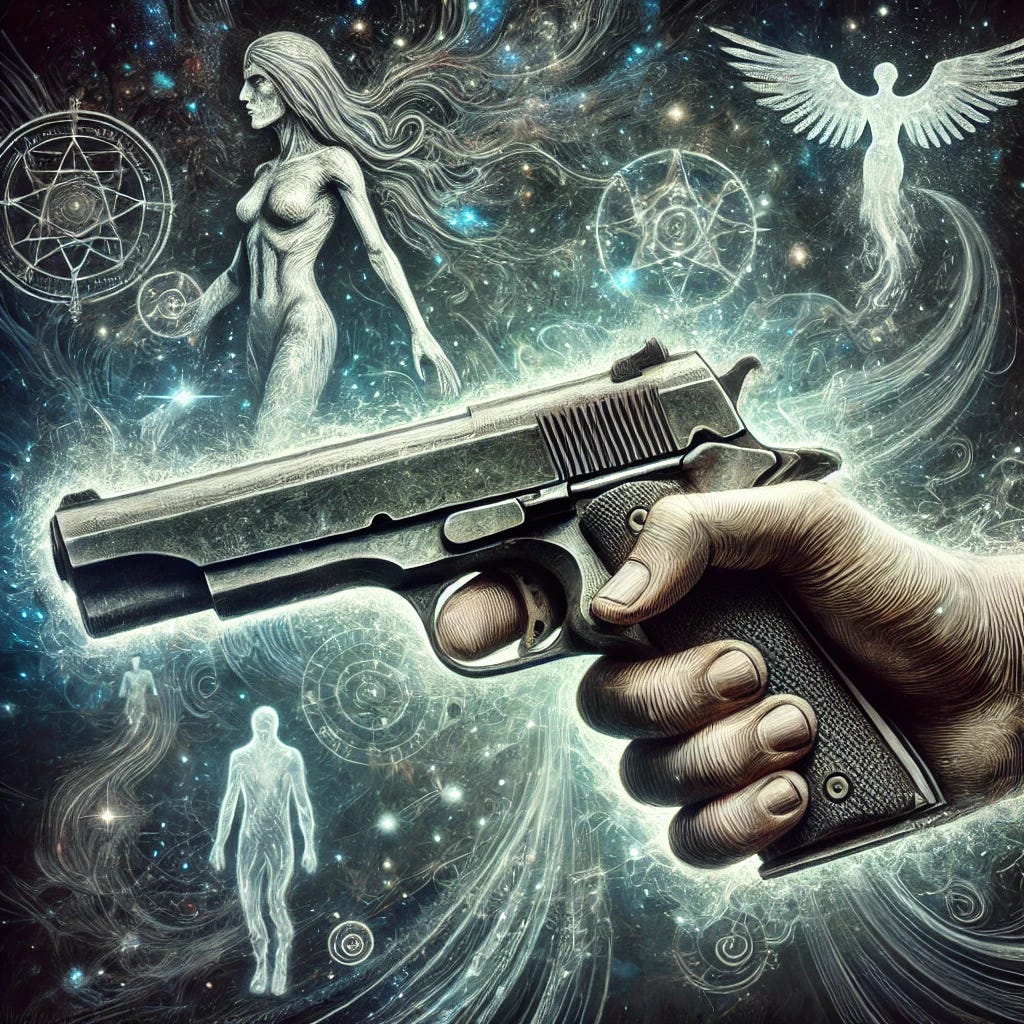

Jim Rutt, quoted above, is a friend of mine. He’s freakishly smart. And in many ways, he’s a product of the Enlightenment. He’s got a unique pistol reserved for anyone who utters the word “metaphysics” when referring to ghosts, spookies, or tarot cards—as opposed to chairs, stars, or quarks.

I join Jim in appreciating the Enlightenment and what it meant for humanity. And when it comes to the causal efficacy of being—to exist is to exert—I think Jim and I mostly walk in lockstep.

I must admit, though, I’m not all reason and observation. I seek the truth but am unwilling to fetishize the scientific modality. I eschew lies but revere fiction.

Jim doesn’t like when people use “noble lies.” He tolerates “useful fictions” when they are designated as such, like a warning label on a pack of cigarettes. Indeed, I tend to lean more in the direction of Jim’s old friend, the great theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman, who understands the importance of retaining, perhaps “reinventing” the sacred, even if the sacred involves no magical essences or supernatural hocus.

Hear me out.

A vital set of distinctions here means we sometimes have to situate ourselves more comfortably in paradox.

Let’s explore the relationship between two dimensions:

x - fact and fiction,

y - truth and falsehood.

An x-axis can represent the former. A y-axis can represent the latter. Readers will now be familiar with this construction, which I employ as a categorization and synthesis tool. A novel framework emerges through examining these concepts along the two axes, which create four distinct quadrants that help us navigate life.

Q1. The Empirical Basis: Fact + Truth

At the cornerstone of human knowledge lies Quadrant I, or Jim’s quadrant, where factual accuracy meets ground truth. This realm encompasses the bedrock of scientific understanding, accurate historical documentation, and mathematical certainty. When researchers document patterns, archaeologists unearth ancient civilizations, or mathematicians prove theorems, they operate in this space of verifiable, publically observable reality. (Perhaps journalists ought to do the same.)

Watson and Crick's discovery and documentation of DNA's double helix structure, based on X-ray crystallography data, represented a verifiable scientific reality that others could independently confirm.

The discovery of the Rosetta Stone provided verifiable evidence of ancient Egyptian language and writing systems, allowing multiple scholars to translate and verify them systematically.

Fermat's Last Theorem, proved by Andrew Wiles in 1995, demonstrates mathematical truth that can be verified through rigorous peer review.

This quadrant is arguably the foundation for human progress, providing the reliable information necessary to advance knowledge and build trust. On such points, we can only agree with Jim Rutt.

But we must remember that this quadrant, while heavy on logos, is light on pathos, mythos, and ethos.

Q2. The Power of Story: Fiction + Truth

Moving into Quadrant II, though, we encounter a territory where fictional narratives transmit deeper truths. Consider how Ancient Greek mythology still illuminates human nature or how Orwell's 1984 warns us about totalitarianism. These stories, while not historically accurate or publically observable like a spectrometer readout, resonate across cultures and centuries because they capture essential truths about our experience.

Here’s an example I found, ironically perhaps, on Jim’s social media timeline:

“I wish it need not have happened in my time," said Frodo.

"So do I," said Gandalf, "and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

― J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Indeed.

This quadrant spills forth with figurative language and timeless wisdom, which says as much about us as a literal, prosaic biography—maybe more. Carefully crafted narratives allow us to explore complex philosophical and moral questions. Otherwise, life is full of useful fictions, especially amid uncertainty.

This quadrant emphasizes pathos, mythos, and ethos but doesn’t discard logos.

Q3. The Realm of Deception: Fiction + Falsehood

Quadrant III represents the dark side of human creativity, where fiction serves not to illuminate but to obscure. This space is populated by deliberately fabricated conspiracies, malicious propaganda, and content designed to mislead rather than enlighten. It is the way of radical social justice, authoritarian deception, and the worst excesses of religious fundamentalism.

Here are some examples:

The NIH has not ever and does not now fund gain-of-function research in the Wuhan Institute of Virology. —Anthony Fauci, almost certainly lying to Congress.

This is a pandemic of the unvaccinated. —President Joseph R. Biden conveyed untruths to the American people when the FDA-EUA Pharma data contradicted this claim.

While some material in this quadrant may be harmless when consumed as pure entertainment, a danger lies in its potential to be mistaken for truth, leading to confused worldviews, misguided acts, and oppressive behavior.

This quadrant emphasizes pathos and mythos, but too often jettisons logos and ethos.

Q4. The Art of Distortion: Fact + Falsehood

Perhaps the most insidious quadrant is the fourth, where factual information becomes a tool of the deceiver. Here, the practitioner seeks to distort accurate data and carefully selects actual events but presents them in a manner that supports false or misleading conclusions. It is the way of modern journalism and, quite sadly, the way of institutionalized science and expertise.

But here’s an example from 51 national security experts:

Perhaps most important, each of us believes deeply that American citizens should determine the outcome of elections, not foreign governments. All of us agree with the founding fathers’ concern about the damage that foreign interference in our politics can do to our democracy.

It is for all these reasons that we write to say that the arrival on the US political scene of emails purportedly belonging to Vice President Biden’s son Hunter, much of it related to his serving on the Board of the Ukrainian gas company Burisma, has all the classic earmarks of a Russian information operation.

This quadrant requires particular vigilance, as its claims often appear credible. Many refer to facts. Statistical manipulation, cherry-picked research, and contextless data points demonstrate how truth can be twisted. Once we discover the distortion, we have to ask Cui bono? Then follow the money.

This quadrant emphasizes logos, pathos, and mythos but too often jettisons ethos.

Practical Applications

Grappling with these quadrants provides a framework for evaluating the information we encounter daily. When examining news articles, social media posts, or academic works, we should ask ourselves:

Which quadrant does this information occupy?

Is factual accuracy being used to reveal or conceal truth?

Does this fictional narrative illuminate deeper realities or obscure them?

Is a master deceiver asking us to live by lies?

This framework reminds us that it can be challenging to untangle fact, fiction, and falsehood. While empirical accuracy remains crucial for scientific and historical understanding, we must also recognize the value of narratives that convey wisdom, conjure emotions, and bolster healthy social coherence. What if we learned that Grand Narratives make for powerful Egregores that logos alone can’t face? At the same time, we must remain alert to blatant fabrications and subtle distortions that can interfere with understanding.

Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic framework of the symbolic, the imaginary, and the real provides another heuristic lens.

The symbolic order, encompassing language, culture, and social structures, shapes our understanding of reality and assigns meaning to facts.

The imaginary order, tied to perception and self-concept, influences how we internalize narratives and construct personal truths.

The real—though sometimes elusive and beyond complete comprehension—represents the unmediated aspects of existence that resist categorization.

If we apply Lacan’s perspective to our quadrant system, we can get richer results as we penetrate fundamental questions of meaning, identity, and reality. And that lets us navigate the interplay between what is and what is at stake.

And I worry this is where Jim Rutt and I diverge.

Our quadrant system offers a practical toolset for critical thinking in an era of information overload and a landscape filled with Geists and Egregores. But it doesn’t remove tools from the table—especially regarding what I have termed “subversive communication.” By understanding these distinctions, we equip ourselves with discernment. Playing with them makes us more powerful communicators in a world where warfare is more often fought with pens than swords. At the same time, we retain the power of mythopoeisis, which is very frequently a collective endeavor.

In short, I want to persuade my friend Jim and you, Dear Reader, that we must master quadrants 1 and 2 and stay attuned to the deceivers’ use of 3 and 4.

Note: Jim Rutt hosts the most excellent Jim Rutt Show.

Note 2: The following dovetails with my case here, though I expect it’ll give Jim a fit.

Jim’s excellent response from FB:

My response to an interesting essay by my friend Max Borders (link to Max's essay in the first comment)

Max, I don’t think our core views are all that different. Sure, we might diverge a bit in our elaborations and preferred methods—like psycho-analysis (eeeewwww!)—but that’s more about style than substance.

Here’s my take on why myth and story ARE indispensable: The world is a monstrously complex, high-dimensional beast. Layers upon layers of emergence stack on top of one another, forming intricate ecosystems of interactions (think of Earth itself: a planet teeming with life engaged in endless games of cooperation, competition, and everything in between). These systems hardly lend themselves to formal analysis. Hell, we can’t even crack the math on something as “simple” as the three-body problem! So, when it comes to navigating this tangled web of complexity, we need tools that go beyond linear, analytical reasoning. That’s where stories and myths come in—they’re humanity’s time-tested way of making sense of the seemingly senselessly complex.

For example, whenever I mentor a young man, I have him read three Heinlein novels in a specific order—Starship Troopers, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, and Stranger in a Strange Land. Why? Because these stories convey nuanced, partially contradictory, and yet overlapping perspectives on "how to be a man." The combined effect of these narratives shapes a kind of gestalt understanding that no formal explanation could replicate. I mean, I could try to distill it all into a bulleted list of lessons, but honestly? That’d miss the point entirely. The real magic lies in how those stories interact with the mentee's unique web of memories, experiences, and cognitive structures. It’s not about spoon-feeding lessons but about sparking something deeper and richer.

Now, take this idea and zoom out to humanity’s relationship with the natural world. We’ve done catastrophic damage to the biosphere by reducing nature’s wild, generative complexity to something sterile and one-dimensional. Case in point: the climax forests of Ohio, once vibrant ecosystems, replaced by endless monoculture fields drenched in chemical pesticides. Why? Because our dominant metric for interacting with nature boils down to a single, cold question: “Does it pay?” Occasionally, we stumble into something positive—like ecotourism—but mostly, this profit-driven mindset slashes nature’s dimensionality down to near nothing.

Here’s the rub: “does it pay?” is the core engine of Game A, a system running on borrowed time and hurtling toward collapse. So, what’s the alternative? Stories and the “sacred,” rightly used and understood, can play an important role.

Imagine if we replaced “does it pay?” with something like this: “The biodiversity and impossibly intricate ecological networks of the natural world are the crown jewels of the universe’s unfolding so far, and humanity is but one thread in that tapestry. Unless there’s a truly compelling reason otherwise, never knowingly reduce net biological complexity.” Can I prove that this is the right way to think? No. But does my high-dimensional, mythopoetic intuition scream that it is? Absolutely.

The question is, can we spread this narrative widely enough to tip the scales—to fundamentally reframe humanity’s relationship with the natural world? Honestly, I don’t know. But it’s worth a try.

Now, let’s talk about the concept of the “sacred.” I’m fine with using that word as a shorthand for how we approach systems of staggering complexity where analytical tools just don’t cut it. But here’s the kicker: this notion of the “sacred” needs to stay grounded. It’s operational, not metaphysical. In other words, it’s a tool—one that’s useful right now, in this particular slice of humanity’s journey. Fast-forward to some distant future where humans (or our successors) wield god-like powers of analysis or no longer care about the biome, and the story might change. And that’s okay.

The strength of invoking the “sacred” lies in its ability to guide practical engagement with complexity. The danger? Forgetting it’s a tool, mistaking it for some unchanging metaphysical truth. If we do that, we risk locking ourselves into dogma, losing the flexibility to adapt our stories when the universe demands something new.

The four quadrants are a good framing, especially when you connect each quadrant to logos, pathos, ethos, mythos. I made a similar matrix once, to try to explain the interplay between curiosity and gullibility. Still trying to refine my use and understanding of the quadrant model.

As to your quadrant of "Fact + Falsehood" . . . I've been pondering that combination a lot over the past year as it relates to evil. The Devil doesn't always lie, but does always attempt to manipulate. And manipulation can be done with things that are technically factual/accurate/correct. If a person looks only for the most obvious lies, that person will be oblivious to a great deal of manipulation.