Lessons from the Persian-Jewish Nexus

There are lessons to be drawn from Cyrus the Great's imperial pluralism.

My Jewish friends keep a longstanding tradition of joking about how some goyim can become 'honorary Jews'—a concept that traces back thousands of years to Cyrus the Great, honored by the Israelites for ending the Babylonian exile.

Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, formed a solid relationship with the Jewish people that has endured for over 2500 years. After conquering the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE, Cyrus issued a decree allowing the Jews, exiled to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar II, to return to their homeland in Jerusalem and rebuild their temple.

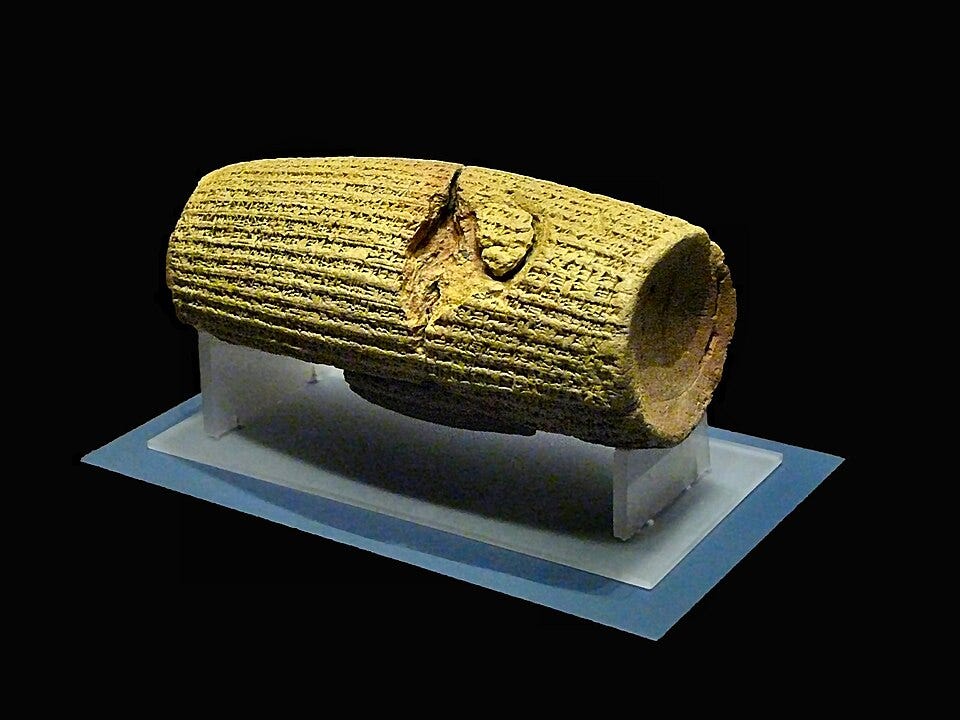

This is documented in the Hebrew Bible (Ezra 1:1-4 and 2 Chronicles 36:22-23) and supported by the Cyrus Cylinder, an artifact that reflects his policy of religious tolerance and repatriation for displaced peoples. The artifact does not mention the Jews explicitly, but aligns with Cyrus’s pluralist policy at the time.

Key points about Cyrus's relationship with the Jews include:

Edict of Restoration. Cyrus permitted the Jews to return to Judah, ending the Babylonian Exile. He authorized the reconstruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, which had been destroyed in 586 BCE.

Support for Rebuilding. He provided resources, including returning sacred vessels looted from the First Temple, and encouraged local governors to assist the returning exiles.

Religious Tolerance. Cyrus's policy allowed the Israelites to practice their religion freely, aligning with his broader approach of respecting the customs and deities of conquered peoples.

Biblical Reverence. In the Hebrew Bible, Cyrus is portrayed favorably, even as a divinely appointed figure (Isaiah 44:28, 45:1), earning him the rare title of mashiach—“anointed one”—extraordinary for a non-Israelite ruler.

This relationship fostered goodwill, enabling the Israelites to reestablish their religious and cultural life in Jerusalem.

The compatibility between Zoroastrianism and Judaism was probably rooted in shared theological and ethical principles. Both religions emphasize a form of monotheism, with Zoroastrianism’s worship of Ahura Mazda and its moral dualism of good (creative) versus evil (destructive) aligning with Judaism’s devotion to Yahweh and similar ethical frameworks.

Both believe in free will and accountability, where Zoroastrianism’s focus on good thoughts, words, and deeds parallels Judaism’s emphasis on righteous behavior. Further, Zoroastrianism’s eschatological concepts of judgment, afterlife, and a future savior resonate with Judaism’s hopes for a messiah.

Both traditions value ritual purity and practices. Scholars still debate the extent to which interfaith similarities influenced Cyrus or the Persian-Jewish nexus.

Still, Cyrus’s religious tolerance, exemplified by permitting the Jews to practice their faith freely, fostered stability and loyalty within his diverse empire. His support for cultural restoration empowered the Jewish community to reclaim their heritage, strengthening their resilience and identity.

By acting as a benevolent leader, Cyrus cultivated lasting goodwill. His diplomatic approach, prioritizing respect for local customs over coercion, demonstrates how mutual respect can build harmonious, enduring connections between different peoples and cultures.

This lies in contrast to those who would eventually overwhelm Persia. Whatever happens in the coming months and years in Iran, we can pray for a return of peace, toleration, and cross-cultural influences between these ancient peoples.

Learn more from Alexander Bard, a modern Zoroastrian from Sweden.