Pirate Radio

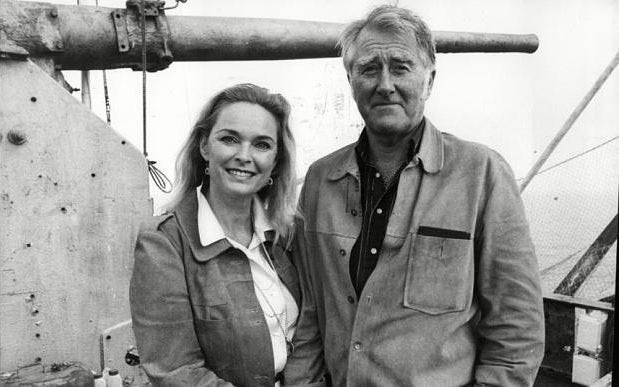

"To the Sea, Freedom!" cried the late Roy Bates whose offshore pirate radio stations and hair-brained Principality of Sealand was a precursor to seasteading.

This piece by Ivan Osario reminds me that the Brits have endured censorship eras before and will endure them again.

For as long as governments have overreached, people have sought escape.

Indeed, some have dreamed of exiting the state completely. From the defunct Republic of Minerva (perhaps the only nation ever to fall prey to Tongan imperialism) to the short-lived Oceania project, a number of individualist mavericks have tried to create societies outside the bonds of established states.

Most have failed.

Yet if any of these ventures can be called a success, it’s the Principality of Sealand. Sealand’s founder, Roy Bates—also known as Prince Roy of Sealand—ruled for 45 years.

He died October 9, 2012.

Bates first took to the seas in the 1960s to establish Radio Essex. He set up his radio station outside of the United Kingdom’s territorial waters, where he could broadcast free from the heavy-handed regulation and censorship that made British broadcasting a dull affair in those days. Whereas most pirate radio jockeys worked from boats, Bates found an abandoned World War II-era platform fort located seven miles off England’s east coast.

Bates’s station was one of many such “pirate” stations. When the British government moved to shut down unlicensed broadcasters operating off its coastline, officials fined Bates the princely sum of £100. Bates declared his independence from the U.K. In 1967, his platform became the Principality of Sealand—and Bates named himself the head of state. His wife Joan would be his princess.

Bates went further than other offshore, unlicensed broadcasters to escape state control. Their distinctly commercial motivation distinguished the British radio pirates from other efforts to escape state jurisdiction. The radio pirates didn’t go out to sea because they simply wanted to be there. Rather, it gave them a competitive advantage over their regulated rivals on shore. (This type of voting with your boat is known as jurisdictional arbitrage.)

Go Wet, Young Man

If future extraterritorial pioneers are to succeed, they should seek a similar competitive advantage over their more heavily governed rivals. One of the latest and most ambitious efforts in this movement is that of the Seasteading Institute, which “work[s] to enable ‘seasteads’—floating cities—which will give people the opportunity to peacefully test new ideas about how to live together.”

[…]

The Seasteading Institute continues, and its community is determined to meet the challenge. But the good news is they needn’t reinvent the wheel, thanks to the precedent set by Bates and his fellow unlicensed broadcasters. They saw an unmet demand for variety in radio programming and discovered a novel way to meet it.

Finding similar niches is the big challenge for modern-day seasteaders, in addition to the technical, engineering, and legal challenges. Modern communication technologies provide new opportunities for entrepreneurs to free themselves from state interventions that are now prevalent throughout the developed world.

The radio pirates’ story is chronicled in University of Chicago historian Adrian Johns’s book, Death of a Pirate: British Radio and the Making of the Information Age. Interestingly, Johns notes that the link between unlicensed British broadcasters and classical liberalism is more than casual. One leading unlicensed radio entrepreneur was an ardent free-marketer. Oliver Smedley, the founder of Radio Atlanta, was a fan of F. A. Hayek intended to break the BBC’s monopoly and helped Antony Fisher establish the influential Institute of Economic Affairs, Britain’s leading free-market think tank.

The political left has long sold romanticized versions of its story—from Alberto Korda’s iconic image of Che Guevara to the self-important narratives from Paris 1968. Bates and his fellow radio pirates offer a welcome antidote to that distorted history. Their story is now seen by most of the public as a valiant struggle against overreaching government bureaucrats—as the 2009 film Pirate Radio shows.

In the 1977 song “Capital Radio One,” punk pioneers The Clash celebrated the fact that, “A long time ago there were pirates, beaming waves from the sea.” Roy Bates went further, as he proclaimed in Sealand’s motto: “From the Sea, Freedom!”

This article by Ivan Osario was originally published at FEE.org.

UK readers note that Between Worlds London is only one week away.

I perfer calling pirates privateers still idk, they were business men just monopoly busting. 🌝 Seasteading would be a super difficult feat that would require a ton of capital.

I admire the spirit of seasteaders, but don't think a floating country is practical, at least with today's technology. How do you get fresh water? Electricity? Food? Medical services? These things, and much more, must be transported in by some means, which can be done by someone with sufficient money to burn, but in my view such a "nation" can't sustain itself without a continuous flow of funds from the outside. I'm afraid we are going to be compelled to work to gain the freedoms that are our birthright here on land.