Positive-Sum World

Let's reimagine and simplify the idea of Natural Law, while revisiting the question of human nature.

Happiness. Harmony. Prosperity. This threefold braid was developed by Chris Rufer, whom I have profiled in these pages. I wish to acknowledge Rufer not only for the concepts but also for how he teaches their interrelatedness. In other words, one without the others is not sustainable. There is something lawlike in this interrelation—especially when we consider their absence: sorrow, conflict, and poverty.

On the question of Natural Law, I find myself at twilight, wading through murky philosophical waters, with logos’s dim lantern to light the way. I had once completely abandoned the idea, having come to think of it as an artifact of a bygone era. But Lysander Spooner—as well as Underthrow readers and other writers—prompted me to reengage the theory. My endeavor here is, then, to simplify the old Natural Law theory so as to strip it down to its essentials without succumbing to reductionism or overreliance on self-evident truths.

Let us begin, though, by acknowledging some shared assumptions. I start with what I take to be our pursuit of happiness, harmony, and prosperity—Rufer’s threefold braid. Such states are not whims but are necessary for civilization. Yet, in our contemplation of such states, we might need to jettison some of Natural Law’s theoretical baggage. Such includes notions that its associated principles are:

Inherent in our natures, implying that more vicious dispositions are not,

Teleological, as if you must live life according to a greater blueprint,

Objective, as one might think of a chair or a quark as being, or

Bestowed by a Benevolent Creator to us, somehow yielding Natural Rights.

The old theory of Natural Law is that principles exist as celestial signposts that can guide our every step. Such notions, while comforting, invite justifiable skepticism. But then our enemies—those advantage-takers who work at odds with happiness, harmony, and prosperity—can use that skepticism as a weapon against us. So, we want to revise our theory a bit.

In such a light, natural law reveals itself not as Divine Legislation but rather as patterns in rich garden soil—complete with nomic constraints—in which the fruits of peaceful human interaction can be cultivated. Consider that only one of the following patterns of interaction gives rise to sustained happiness, harmony, and prosperity:

Positive-sum,

Zero-sum, and

Negative-sum.

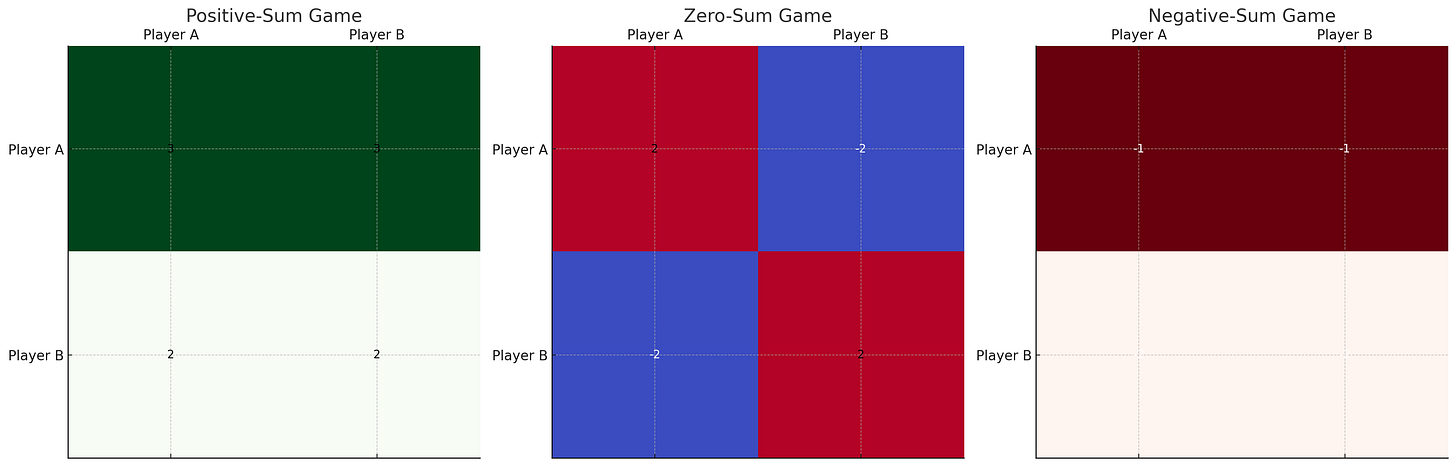

The chart above represents the differences between positive-sum, zero-sum, and negative-sum interaction mechanics:

Positive-Sum Rules—Both agents can achieve gains simultaneously. The outcomes (e.g., 3, 3 or 2, 2) indicate that when both agents cooperate or engage in beneficial actions, they both receive positive payoffs, contributing to overall increased welfare.

Zero-Sum Rules—The gain of one agent is exactly balanced by the loss of the other agent. The outcomes (e.g., 2, -2 or -2, 2) illustrate that one agent’s gain is the other's loss, leading to a situation where the total payoff is zero when summed.

Negative-Sum Rules—Both players experience losses. The outcomes (e.g., -1, -1 or -2, -2) show that interactions can lead to a scenario where both parties are worse off, resulting in a decrease in total welfare.

The chart above shows how different game mechanics influence the outcomes for the participants. Such highlights the vital importance of the nature of interactions in determining the creation and distribution of benefits (or losses) among the participants.

Relevant examples include:

Positive-sum interaction—Voluntary cooperation and entrepreneurial markets.

Zero-sum interaction—Compulsory income and wealth taxation and redistribution.

Negative-sum interaction—Much of politics, political lobbying, and war.

Positive-sum interactions, those voluntary associations that generate a net benefit for all participants, are our North Star. They are the embodiment of our shared assumptions, that is, the framework through which Rufer’s threefold braid is actuated. Such unfolds from agents (people) following embedded rules, the foremost being:

To abstain from initiating harm—i.e., to make others worse off—through violence, theft, fraud, or the threat of these.

Of course, such abstinence creates more opportunities to collaborate for mutual benefit in the market and to cooperate in one’s community with others in purposeful acts of compassion.

Some critics will argue that zero-sum arrangements are necessary for positive-sum arrangements to be realized. But this is an argument from incredulity, not possibility.

We mustn’t shy away from an uncomfortable truth: Zero- and negative-sum interactions persist and are routinely justified by the powerful. At some point, we will have to think of the powerful as enemies. Involuntary associations—such as those between the ruling class and the ruled—yield little to no net good and detract from our individual and “collective” well-being.

Yet most people tend to think of zero- and negative-sum interactions not only as necessary evils but as good and just. A species of religious zeal burns in the minds of the many such that—instead of thinking about how politics actually works and what sort of people politicians really are—they want to live in Abstractionland where zero-sum politics "is simply the name we give to the things we choose to do together," you know, for the “common good.”

Our critics might retort that game theoretical constructions are abstract, too. But once we open our eyes to the destructive nature of these patterns in the real world, we awaken. One need only look around.

We go from accepting our lot as a herd animal to engaging with others in self-organization. It is here, in the efflorescence of endeavor, enterprise, and exchange, that natural law is revealed. Its wellspring is not in the ethereal realm of objective morality but rather in the concrete reality of applied instrumental rationality.

Such rationality is not the cold, calculating logic of machines but can be a vibrant, intersubjective expression of our shared values—agreed upon through a combination of real and tacit social contracts—in the Magistarium of Ought. It is through such agreements that we navigate the complexities of human interaction and that we define the boundaries of our collective pursuit of the threefold braid.

Natural law, then, is not a set of immutable decrees handed down from a transcendent deity but perhaps the unfolding of an immanent, lawlike nature—which might well also be Y’WEH—and our recognition of it. We—the seekers of happiness, harmony, and prosperity—move toward an evolving consensus of those committed to positive-sum interactions and, thus, to the co-creation of a world in which everyone may flourish.

Are We Good-Natured?

In our quest for a simplified theory of natural law, we must accept the complexity of human nature, the diversity of human desires, and the intricacy of human relationships. We must recognize that our assumptions, while foundational, are not the end of inquiry but the beginning. The threefold braid is our normative compass, not a Platonic Utopia where all questions are answered and all conflicts resolved. Still, to get a deeper understanding of the principles that govern our interactions and shape our world, we need to carefully consider the central questions of human nature.

Consider this passage from Paul in the New Testament:

For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. For we know that the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now. And not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies. —Ro. 8:20-23

This passage strikes me as dualistic in that Paul imagines humans as noetic beings animating corrupted bodies. In the interest of being, well, ecumenical, though, I want to explore the wisdom here.

What prompted this?

One of our favorite readers, David—a faithful Christian—sent me an interesting and perhaps subversive post from an Orthodox priest, Fr. Stephen Freeman, which includes Paul’s quote from Romans, cited above.

Freeman writes:

The death (bondage to corruption) that afflicts us all is not a bondage of our nature, but a bondage contrary to our nature. By the same token, we can describe this as a bondage that seeks to impact our “goodness.”

Admittedly, I had a hard time with this bit for reasons similar to my concerns about Paul’s passage. Then, Fr. Freeman makes an important interpretation.

Here, I think, it is important to see not just the bondage, but the “groaning” as well. What St. Paul describes is not a creation locked in passivity, quietly embracing its bondage to corruption and death. At every moment, creation resists this bondage. It groans and labors to bring forth the good, despite every limitation set upon it.

How very Nietzschean!

This struggle and groaning is where I would draw our attention. It is a sign and testament to the essential goodness of God’s creation that has not been, nor ever can be erased. Creation pushes back against our feeble efforts to control it. Asphalt and conrete yield to tiny sprigs of grass whose groaning has overcome the weight of our technology. Every Spring, what cycles of weather have suppressed comes back with a vengeance of life. [Emphases Mine.]

Some spots in the above might have been plucked from Emerson or, again, Nietzsche, dualism notwithstanding.

After all, Nietzsche’s hostility towards institutional Christianity, while it includes metaphysical hostility towards Platonism, shares Fr. Freeman’s insistence that a) there is a generative nature in human beings and, indeed, life, and b) too many Christians falsely believe and teach a misinterpretation of Jesus in doctrine.

Fr. Freeman writes:

There is a common mistaken notion about the fall (the sin of Adam and Eve). That mistake is to think that the fall somehow changed all of creation and human beings from a state of original innocence into an altered state of evil and corruption.

That’s certainly contrary to so much of what passes as Christian doctrine today.

Despite some differences in theology and metaphysics, we can agree that most of us are generative beings who seek happiness, harmony, and prosperity—our threefold braid. The troubles lie in that too many people are willing to sacrifice one part of that braid to get the other parts. Here, some have destructive natures. But like Christianity’s Triune God, you can’t have one without the others—at least not for long.

For now, I will pass over any disagreements about the ultimate nature of good. Again, if we are to have enough solidarity to face down such power as threatens us today and our children’s futures tomorrow, we must be more ecumenical.

In such an audacious endeavor, we must channel the spirit of both Nietzsche and Fr. Freeman—to be unapologetic and unflinching in our pursuits. It is only through such relentless inquiry and experimentation that we can hope to approach answers to the question: How are we to live? How are we to live together? And, of course, how are we to underthrow our enemies?

We uncover the patterns of positive-sum interaction that bind us, heal us, and make us more generative together.

"Again, if we are to have enough solidarity to face down such power as threatens us today and our children’s futures tomorrow, we must be more ecumenical."

Absolutely agree. I have been trying to cultivate civil debate under a general rubric of cooperation. The "narcissism of small differences" ends up being a perennial problem, but people of goodwill, with a focus on a larger objective, must do our best!

At the heart of Natural law is a simple/ complexity. In order to thrive life seeks to reverse entropy, which is the source of Positive Sum outcomes. But always there is the Yin of entropy and decay which is also necessary. We have to understand the Primacy within Nature to understand Natural Law.