Principles of Market Fundamentalism, No. 2: Exchange

This week, we turn to the beauty and elegance of 'You scratch my back, I'll scratch yours.'

Exchange <

Rules

Money

Entrepreneurship

Inequality

Ecosystem

Emergence

Transaction Costs

Principle Two: Voluntary exchange makes both parties better off.

Far from being a problem, whole economies operate according to people’s subjective valuations. Consider a circumstance in which there is a double coincidence of wants: If you like my X more than your Y, and I like your Y more than I like my X, we should probably make a trade. Each of us will be better off if we do.

This formulation is deceptively simple. In the absence of force, fraud, or bad information, exchange occurs lawlike when two parties believe they will be better off than if they do nothing. Of course, anyone can get buyer’s remorse, but that is irrelevant to the principle that tells us exchange is proof of perceived mutual benefit.

As the economist and philosopher Ludwig von Mises famously wrote:

The consumers patronize those shops in which they can buy what they want at the cheapest price. Their buying and their abstention from buying decides who should own and run the shops. They make poor men rich and rich men poor. They are supreme. Everybody serves them. They are the customers.

And, of course, Mises is channeling Adam Smith, who wrote:

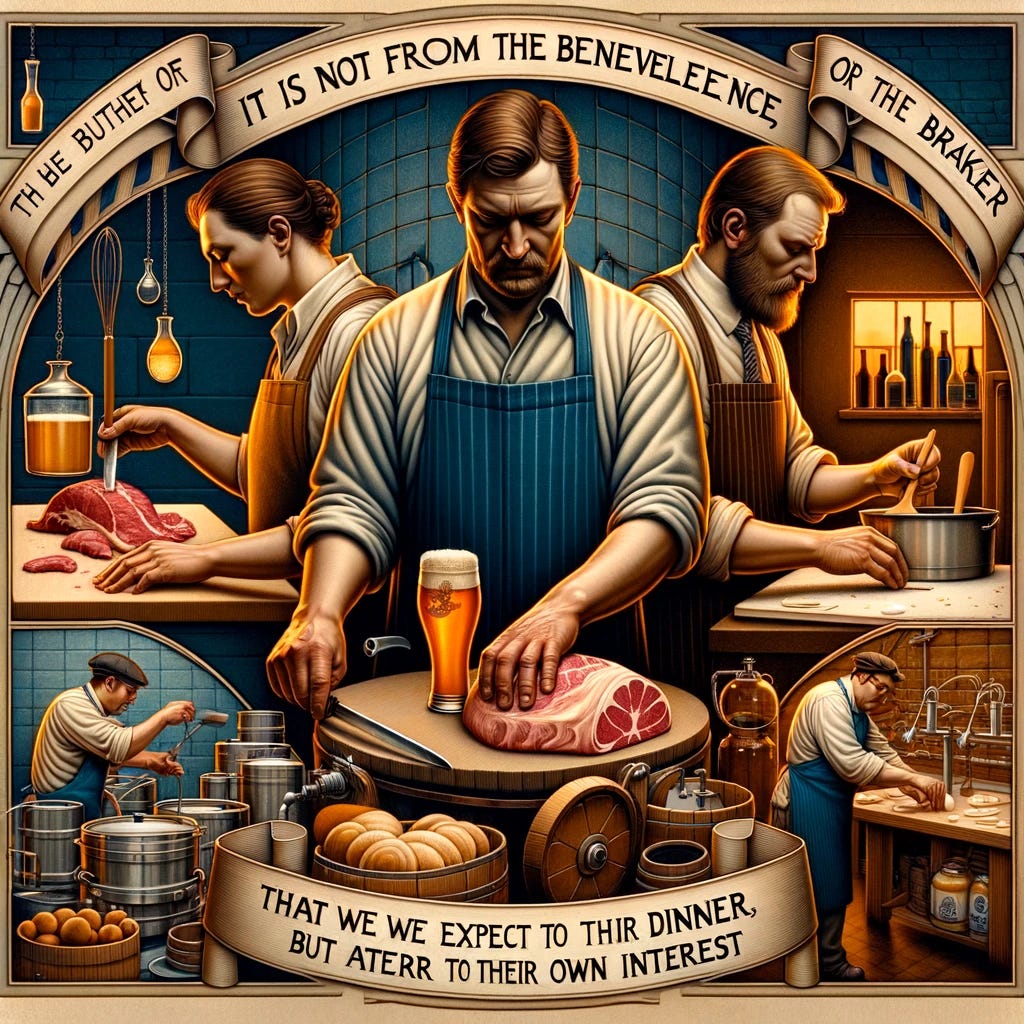

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

High Minds don’t like all this invisible-hand talk.

The Trouble with "Evonomics"

The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design. —F. A. Hayek One would think that a full appreciation of evolution and emergence in the context of modern economics would be enough to mute the temptations of High Modernism—James C. Scott’s term for the ideology o…

Yet, paradoxically, one of the virtues of exchange is that it prompts people who might otherwise be enemies to cooperate. As Bastiat is credited with saying, “When goods don’t cross borders, soldiers will.”

Even when the parties have not invested in production, exchange alone can improve the economy.

Imagine that one day various items fell like manna from above. People would snap up items quickly to prevent others from doing so. Under this first ‘distribution,’ people are not likely to be terribly satisfied, especially if they can see what items others are snatching up. Manna falls at random, after all.

But when people start to trade, more and more find satisfaction, which means they become wealthier through trade alone. Indeed, the more we can see of the market, the more likely any given person will satisfy her wants—at least if she has something to trade.

Excellent. Also where can I buy the Marx shirt? 😁

I may be peeking at the end of the book here, but I'm guessing the surprise twist is that the sum of all subjectivities is a kind of decentralised and emergent objectivity? What the lettered and high-minded sought, but could not find, because they wanted to impose it from the top down?