Rage Against the Machine Metaphors

The machine metaphor is a persistent scourge in characterizing the economy and society. Society-as-living ecosystem is the most truth-conducive metaphor. Sadly, too few use it.

As we discussed here, the machine metaphor characterizes systems as predictable, centrally controlled, and static—designed with specific functions in mind. In contrast, a complex economy, like a living ecosystem, is decentralized, evolving, and dynamic—shaped by countless interactions and adaptations. Machines can be understood by breaking them down into individual parts, whereas economies display holistic properties where the whole cannot be easily deduced from its parts. So, using a machine metaphor falls short in capturing the intricate nature of a living ecosystem such as an economy.

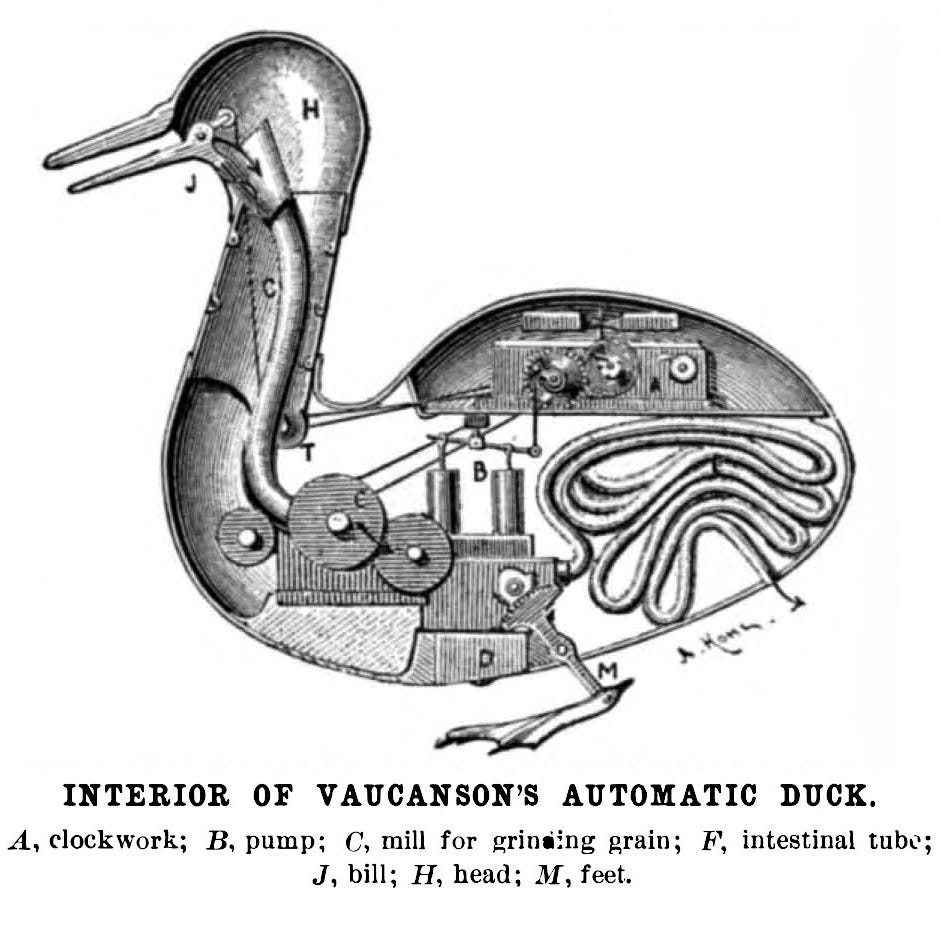

In the early 1700s, French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson dazzled audiences with a series of eerily lifelike automatons. His masterpiece came in 1739 when he unveiled a "Digesting Duck." The duck could flap its wings, splash in water, and nip grain from someone's hand. It would even poop pre-loaded pellets onto a platter. Inside the duck of gold and copper was powered by weights that used gravity to turn a collection of levers. First-of-its-kind flexible rubber tubing resembled entrails, giving the impression that the duck could swallow and digest food. The duck wowed the people of France and Vaucanson won widespread praise. When I think of certain High Minds under the spell of the machine metaphor, I am reminded of the phrase "If it walks like a duck…" But as clever as Vaucanson's contraption had been, it was not a duck. And neither society nor the economy is a machine.

If It Quacks Like a Duck

To put all this into perspective, consider that economists built a machine designed to model the British economy in post-war Britain. It's called the Phillips machine. Like the Digesting Duck, the Phillips machine was greeted with much fanfare in 1949 when it was unveiled at the London School of Economics. The machine used hydraulics to model the workings of an economy but now looks like a mad scientist's work.

"The prototype was an odd assortment of tanks, pipes, sluices and valves," writes Larry Elliot in The Guardian,

with water pumped around the machine by a motor cannibalised from the windscreen wiper of a Lancaster bomber. Bits of filed-down Perspex and fishing line were used to channel the coloured dyes that mimicked the flow of income round the economy into consumer spending, taxes, investment and exports.

Keynes might have been delighted by the device had he lived to see it. By contrast, Friedrich Hayek would have shaken his head at such a Rube Goldberg contraption. And maybe he did.

Hayek left the London School of Economics for the University of Chicago in 1950.

Few macroeconomists are willing to admit that their models—despite greater sophistication—are infected with the machine meme. Most seem to think we just need better models. Rogue economist

objects, though. Kling argues that mainstream macroeconomics is "hydraulic.""There is something called 'aggregate demand' which you adjust by pumping in fiscal and monetary expansion," writes Kling.

High Minds such as Nobel economist Joseph Stiglitz have also fallen prey to economic scientism. They want to build and run the machine from Washington. Stiglitz argues we should scrap market entrepreneurism entirely and "recognize that the 'wealth of nations' is the result of scientific inquiry...." A more concise definition of scientism could hardly be given. But that view is made all the more pernicious by the false promise of economic modeling and its attendant metaphors.

Interviewed for a Newsweek story, Paul Krugman once said that what drew him to economics was "the beauty of pushing a button to solve problems."

As we move into an uncertain future, it's not at all clear the High Minds have learned their lessons. An internet search of the phrase fix the economy returns too many results to count here. Building an economy yields even more.

Deus ex Machina

Let's bring back economist Friedrich Hayek for an encore. Having witnessed the technocratic impulse of the twentieth century, Hayek concluded in his 1974 Nobel lecture that so much of economics is afflicted with what we referred to earlier as scientism. He said,

It seems to me that this failure of the economists to guide policy more successfully is closely connected with their propensity to imitate as closely as possible the procedures of the brilliantly successful physical sciences—an attempt which in our field may lead to outright error. It is an approach which has come to be described as the "scientistic" attitude—an attitude which, as I defined it some thirty years ago, "is decidedly unscientific in the true sense of the word, since it involves a mechanical and uncritical application of habits of thought to fields different from those in which they have been formed.

This critique is as relevant as ever.

"When any theory is treated as sacrosanct," writes Michael Rothschild in Bionomics, "its proponents assume the role of high priests, and strange things happen in the name of science."

To recap our earlier discussion, the whole idea of building, fixing, running, pumping, regulating, or designing an economy rests on the idea that society can be ordered by intelligent design. That is if the right guys are at the buttons.

But there are no buttons. There are no pumps. Neither central bankers nor government bureaucrats can fly in as deus ex machina to correct a complex economy without unintended effects. Why? Because the relevant forms of knowledge are not concentrated among a few elites but rather dispersed among billions of people and millions of organizations. As such, the economy cannot be engineered. It is dynamic. It is organic.

This insight allows us to find out just what's wrong with the language experts use to talk about the economy and our society. Maybe it's time for us to admit that our living flow systems have no mission control. Once we accept that, the machine metaphor sputters, then stalls.

Before we turn away from the problematic machine metaphor, we should warn that other language games are being played, and they too are misleading. For example, we have society as a patient and the technocrat as a doctor. Have you ever heard the phrase 'our ailing economy'? How should we prepare the patient for surgery?

There is society as children and technocrat as a parent. The traditional right provides the paternalistic law and order of a dad. The conventional left provides the unconditional care of a mom.

Mom and Dad always fight.

Some view social policy as an act of creation. The metaphor is government as God. The latter is omniscient and omnipotent, extending to presidents as messianic figures. While no metaphor works as an exact mapping of reality, some are better at revealing relevant aspects of the truth than others.

Society as a living ecosystem is the most truth-conducive metaphor.

Sadly, too few use it.