Introduction: The 48 Laws of Peace

In this new series for paid subscribers, I offer contrasts to Machiavellian strategies for work and life, calling readers to learn and practice virtues for a good society. This, too, is underthrow.

How are we to live? It’s one of humanity’s ancient questions. Yet answers can be elusive. The question extends to myriad contexts but is especially salient when navigating life at work and home. I hope the 48 answers I provide in this series, tentative as they are imperfect, can be a helpful guide.

Still, you might have already noticed that this is a series of contrasts.

Laws of Power

Author Robert Greene has answers of his own to the question of how we are to live. Greene offers a manual for taking a darker path in his bestselling book, The 48 Laws of Power. People have embraced its messages with a peculiar zeal thanks to its focus on pursuing power through unconventional means. Author Ryan Holiday, famous for repackaging Greek stoicism, apparently learned under Greene’s tutelage before writing his own bestseller, Trust Me I’m Lying.

It’s understandable.

If one is unhappy at work, feels put down, or is held back by circumstances, one might be tempted to become more Machiavellian. The 48 Laws of Power offers strategies that encourage readers to assert control in shitty life situations, but it also calls them to explore the shadowier aspects of their natures. Greene advocates measures such as espionage and manipulation to achieve success or gain influence, challenging conventional mores. And, while the book is not explicitly spiritual, The 48 Laws of Power encourages readers to deviate from virtue and cultivate more sinister forms of self-empowerment—like the darker arts of the left-hand path.

But that comes at a cost.

Just as practicing yoga or martial arts shapes one’s body and mind in ways that keep one healthy, Machiavellian practices can shape one’s dispositions and actions—with antisocial results. Indeed, as more people pursue power through means that stray from virtue, they risk reshaping their spirits until they become something mutated, a simulacrum of who they were or once aspired to become.

When millions of people follow advice such as create chaos to seize control—or act dumb to gain an advantage—whole nations risk turning their societies into something grotesque.

Simulation Games

Before imagining some dystopian social order, consider the context of advanced simulation games: It’s no accident that the two major strategic approaches are cooperation and defection. These concepts revolve around the kinds of choices players make when interacting with others in various scenarios. Such decisions can significantly impact the outcomes.

Cooperation refers to a strategy in which players opt to work together and coordinate their actions to achieve mutual benefits or reach optimal outcomes. In cooperative scenarios, players may form alliances, share resources, and collaborate to maximize collective gains. Cooperation usually requires trust, communication, and a willingness to sacrifice short-term benefits for long-term success. Players who cooperate can create win-win situations, in which all parties benefit more than if they were to act alone.

Defection, on the other hand, involves players acting in their own interests, perhaps dismissing the interests of others. Defectors prioritize maximizing their gains at the expense of others. This strategy can lead to suboptimal outcomes or conflict, as players engage in unhealthy competitive behavior, withhold resources, or break agreements. Defection can be driven by a lack of trust in others' willingness to cooperate or by a desire to exploit vulnerabilities in the system.

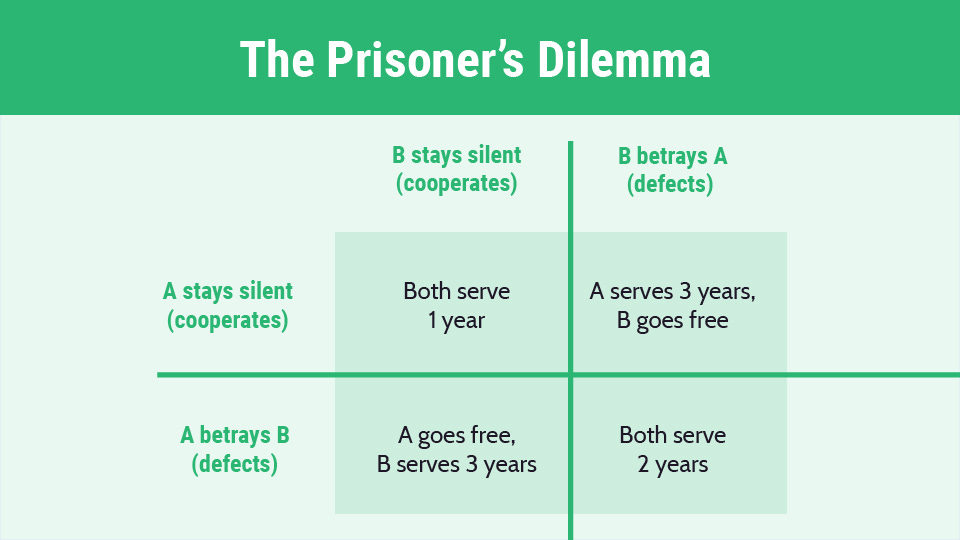

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a classic example that illustrates the tension between cooperation and defection. The exercise highlights how rational individuals may opt to defect despite the potential for mutually beneficial cooperation. In more complex games, players often navigate a spectrum between these two strategies, adapting their choices based on their opponents’ actions and the dynamics of the game environment.

Welcome to real life.

My fragile hypothesis is that when people apply either of these two basic strategies in the real world, by degree, the result can be a tale of two societies: one more harmonious; the other more dystopian.

An Infinite Game

In his own classic book, James Carse similarly taught us to see the difference between finite and infinite games.

Finite Games are games with a clear beginning, ending, and objective. The players are known, the rules are fixed, and the outcome is an endpoint—usually with winners and losers. People play finite games to win. But once they've won, they’re done. Such games are prevalent in competitive environments where success is determined by beating others.

Infinite Games are games with no defined beginning or end; the objective is not to win but to keep playing. The rules can change, and new players can enter the game anytime. An infinite game is about perpetual play, where the goal is to continue the game itself. This mindset usually applies to personal development, commercial sustainability, or any long-term vision emphasizing continual growth and adaptation.

Politics is a finite game. Office politics is no different. Neither is international relations. Those who thrive in politics may well adopt the Machiavellian Path. But The 48 Laws of Peace series is intended as an antidote. Instead of pursuing power, we explore ways to practice virtue—to become a wizard of the Infinite Game.

Upgrade to a Paid Subscription now to access the 48 Laws of Peace series and all the other great Underthrow content.