The Moral Languages of Babel

We must learn to speak the different moral languages of freedom or we will remain divided, scattered, and confused as the powerful keep us under cloven hooves.

The following is the product of a debate I had with an objectivist friend, Craig, many years ago. As the world has become decidedly less free in the decade since my friend and I had this debate, I thought it important to share this pragmatic case.

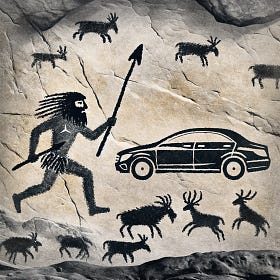

Only two forces of change in this world matter—compulsion and persuasion. Those who love freedom shun compulsion. But to be persuasive, we must be capable of guiding people down different paths. To increase the odds of bringing more people into our orbit, we must learn to think along multiple moral dimensions. In other words, to be freer, we must learn to speak in various moral languages. Why? Because evolved beings operate in those moral languages, and we have to persuade enough of them for any of this to matter.

Indeed, if we were to rely on a single moral foundation—say, rational egoism—we would be vulnerable. To see why, let’s examine the objectivist position.

Premise One: Initiating force is wrong because it stops someone from acting on his rational judgment, the basic means of sustaining (and furthering) his life.

This premise can be true at times, but it is susceptible to attack as a generalized ethic. For example, few take seriously the notion that a 20 percent tax on Warren Buffett’s income deprives Buffett of the means to sustain his life. If it takes $40,000 per year to sustain his life, then Buffett has about 3 million times more money than he needs. Premise one, therefore, may actually provide indirect justification for the statist to take Buffett’s wealth. I don’t think we want that.

Now, if we argued that taxing Buffett diverts capital that sustainably keeps people out of poverty—through employment and so on—we’d fall outside the scope of Premise One. (I’ll pass over the problem that some interventions are justified by stopping people from acting on their irrational judgment.)

Premise Two: Egoism holds that each individual should pursue his own life-serving values, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself.

Suppose there is something about Buffett’s happiness or life-serving values connected to his many assets. One might argue that taking a portion of Buffett’s wealth deprives him of such and that an egoist ethic gives primacy to Buffett’s happiness. There is an important insight here.

But is it strong enough to function on its own?

Even if we suppose that rational egoism justifies the connection between happiness and wealth, we’d have to show both that taxing Buffett made him less happy and that such a consideration was more important than some competing value—for example, keeping certain people out of desperate poverty. Remember: This is about the pragmatism of persuading others. So even if readers of this publication think personal happiness for billionaires is more important than poverty alleviation—because of a doctrine—most people do not. One will have a hard time getting beyond someone’s felt indignation with what egoism “holds.”

Premise Three: A related and even more widely accepted moral code, altruism, holds that the standard of morality is self-sacrificial service to others.

Now, several alternative moral considerations compete with rational egoism, and these moral dispositions will be wired deep within people.

The Origins of Envy

When Envy breeds unkind division: There comes the ruin, there begins confusion. – Shakespeare, Henry VI Man will become better when you show him what he is like. – Anton Chekhov They’re the 99 percent. They have a set of demands as clear as the streets they occupy. They’ll hold a vigil for Steve Jobs, throw pies at Bill Gates, and may vote reflexively for s…

Altruism is among them. Should those defending personal and economic freedom leave these off the table?

What’s more, objectivists do not always distinguish between morality and politics. So, an ethic of self-sacrifice (à la Mother Teresa and Auguste Comte) does not automatically translate into a politics of forced redistribution.

Instead of accepting the objectivist’s definition of altruism as a universal duty to sacrifice to others, suppose we simply acknowledge that people can have moral instincts to be concerned for the less fortunate. Indeed, if we accepted rational egoism as the single moral foundation for liberty, we would not be able to defend free-market participation because entrepreneurship and markets are the most effective poverty fighters—due to their sustainable production and trade patterns. The rational egoist is not comfortable with such consequentialist thinking. But surely some of this is important to defending human freedom.

Premise Four: The proper standard for determining whether an action, policy, or institution is good or bad, right or wrong, is the factual requirements of the individual’s life.

Factual requirements? I will pass over my concern that the rational egoist risks decapitation by Hume’s Guillotine, Kant was certainly right that “ought implies can.” That does not suffice to derive a value from a fact.

Egoism, an ethic stating that each individual should pursue his or her life-serving values, is supported by the idea that people must act according to their own minds. And this justification, says my counterpart, has a basis in fact—that is, what is required for the individual to live.

We’ve already shown that not all initiation of force (taxing Buffett) deprives people of their means of life in any profound sense. As importantly, though, the reason people need moral values at all is not merely to live. We need moral values to live with each other. Most people want to live in peace. Assuming a conversation with those who want peaceful coexistence, we need to be able to discuss all sorts of different moral frameworks that operate, at least, to minimize conflict.

Thus, a single moral foundation is not enough.

Value pluralism

And that is the basis of my rather different ideas about what it means to live free. No—not basis—but rather a “constellation of beliefs.” As we float out in the moral universe with each other, often moving in different directions, we must do our best not to collide. And that requires understanding people with different perspectives.

If we’re going to gain and preserve a free society, we’d better be prepared to speak in a variety of moral languages: utilitarian, virtue, rights-talk, and so on. Why? Because people—even freedom lovers—begin at different starting points. And you want those freedom lovers to coalesce in solidarity, not divide themselves by doctrinal fundamentalism or zealous commitment to The One True Way.

The main problem with any attempt at grounding some political philosophy on a single foundation is that said foundation becomes an easier target: Do away with that spindly column, and the whole edifice comes down. If you have a constellation or web of justification, it can be stronger.

Such is not to argue that we can’t take issue with other moral languages. It is rather to acknowledge that they’re out there—and they motivate people. Put another way: Assume we all think human freedom is good—that is, we value it, and we’ve joined together in a community. Will that community find enough members and a sufficient degree of solidarity if membership is contingent on everyone embracing a single foundational belief?

That we’re all reading this publication demonstrates my point. To widen and deepen our community, we’d better learn to justify freedom across several dimensions of value—and integrate them. One person’s axiom can be another’s antagonism. If we’re to convince others that freedom is the goal, we must convince them that freedom makes space for any number of virtues to be practiced or values to be expressed.

If we don’t, the powerful will surely prevail.

A version of this article originally appeared at The Foundation for Economic Education.

I often talk about the 'moral multiverse' to emphasise some of the points you make here.

Yes, multiple languages and vectors = good.

That said, the notion that coercive force must not be initiated really does, somehow, need to be an axiom. I agree that we must, as a species, move past the notion that there is 'one true way.' Way past! But that one axiom does, somehow, need to be a universal rule.

I have sought to justify it differently from others. I root it in the absence of ontological (birthright/automatic) authority. (Setting aside parental authority, which is the result of natural facts), I contend as a core premise that no one has ontological authority over any other. No one is born with the right to rule. All authority must thus either be granted or imposed.

If we accept that, and we accept the definition of authority in premise 1 (which I contend is a reasonable definition), we can do this:

1. Authority is the license to compel actions and choices.

2. No one has ontological authority over others.

.˙. No one has the ontological authority to compel the actions and choices of others.

We might also do it this way, since compelling the actions and choices of others generally requires coercive force:

1. Authority is imposed upon the unwilling by coercive force.

2. No one has ontological authority.

.˙. No one has the ontological authority to impose coercive force upon the unwilling

Since we want to add moral weight to these facts, we can next do this…

First, we acknowledge the existence of free will. Whatever its limitations, only you can think, act, and choose for you. It is exclusive, inalienable, personal control over your thoughts, choices, and actions. So…

1. Exclusive, inalienable personal control over thoughts, choices, and actions (free will) grants to each individual exclusive, dispositive decision-making power over his own body and life.

2. The primary characteristic of property rights is exclusive, dispositive decision-making power.

.˙. Free will grants to each individual property rights over his own body and life.

This gives us self-ownership, which is naturally exclusive and inalienable. Then…

1. Self-ownership is violated by the initiation of coercive force.

2. No one has the ontological authority to impose coercive force upon the unwilling

.˙. No one has the ontological authority to violate the self-ownership of the unwilling.

Thus, we have a moral defense of the NAP, and of rights (which are, in essence, expressions of self-ownership).

If Hume has a problem with any of this, he can feel free to call my office.