When N.S. Lyons Went Too Far (Part Two)

National Conservatism is retrogressive. A loving monarch is still a dangerous monarch. And patriotism without principles is un-American.

The traditional right provides the paternalistic law and order of a dad.

The conventional left provides the unconditional care of a mom.

Mom and Dad always fight.

—from “Rage Against the Machine Metaphors”

Picking up our discussion of

’s ode to love of country, we resume to find him assessing post-war Europe. By banishing all the strong gods, says Lyons—family, nation, truth, and God—Europe went too far.In this belief post-war leaders embraced the legacy of Thomas Hobbes, who had viewed the wars which upended his own century as a product of the state of nature – the “war of all against all” – that constantly threatened to emerge from the pride and spiritedness (thumos) of mankind’s base natural personality. He saw the solution to this risk as man’s submission, out of fear, to the absolute power of a political leviathan – but also to an anthropological project, a program of metaphysical reeducation to turn man’s eye away from any summum bonum and downward toward only the fearful summum malum of struggle and death.

Hobbes’s legacy looms, but not quite in the way Lyons argues.

In some respects, Hobbes started the liberal-enlightenment project, which inspired the founders and eventually gave us the United States. In other respects, the powerful have used Hobbes to seize power and make political mischief.

I offer the following explanation from “Fear’s Intellectual Fruit”:

Though Hobbes is considered a proto-liberal when his work is taken as a whole, his Leviathan Formulation threatens liberalism itself. That formulation goes:

Rule. Assume that sovereignty—that is, powerful rule—functions as a kind of monopoly over some territory (and its people);

Rules. People living together can only be a nation if they have a common system of rules;

Ruler. A common system of rules can only exist if those rules come from the same source, a ruler—an authority of such power that only it has the final say.

Rule. Rules. Ruler.

Political theorist Vincent Ostrom insists this sort of relationship,

must involve fundamental inequalities in society. Those who enforce rules must necessarily exercise an authority that is equal in relation to the objects of that enforcement effort. (Emphasis mine.)

Those objects are, well, the rest of us.

Of course, Leviathan is meant to be powerful enough to strike fear in all the people who would disobey, squabble, or upset the peace.

But is post-war Europe a product of Hobbesian preoccupation with the summum malum or an idealistic product of Kant’s perpetual peace? I would argue it’s a mix, but with the latter animating Europe and the former animating the US.

America became the de facto Leviathan. Europe was to be the architecture of perpetual peace. Together, they functioned as Good Cop, Bad Cop until 2025.

Yet far from an obsession with all that’s illiberal, American power was fueled not only by strong gods but also by the incentives of the military-industrial complex. Along with a sense that God endowed America to wield the scepter of global hegemony, there was profit in hegemony. Only after the failed Vietnam War did the hegemon start to navel gaze. Strong gods persisted, though, among a people who were okay with US unipolar power and frequent interventions. *USA! USA!*

Lyons shifts focus to a different egregore, though—one that sprang up in the academy.

With Hitler having firmly established himself as the summum malum of the post-war order, the liberal establishment embarked on their own version of Hobbes’ political-anthropological project. Seeking to dissolve the traditional “closed society” they feared was a breeding ground for authoritarianism, this “open society consensus” drew on theorists like Adorno and Popper to advance a program of social reforms intended to open minds, disenchant ideals, and weaken bonds.

I get uncomfortable when I see conservatives refer to anything as “liberal.” America’s favorite anti-liberal Papist, Patrick Deneen, equivocates when he expresses his distaste for liberalism, probably because he loathes both forms. However, liberalism as a freedom project and liberalism as ideological leftism are two very different doctrines. Yes, Popper and Adorno both lived through totalitarian horrors. But whatever you think about Karl Popper, he doesn’t belong in the same sentence as Theodor Adorno—that is, unless you’re trying to equivocate.

But let’s give Lyons the benefit of the doubt.

New approaches to education, psychology, and management sought to relativize truths, elevate “critical thinking” over character development, cast doubt on authorities, vilify collective loyalties, break down boundaries and borders, and free individuals from the “repression” of moral and relational bonds. Soon only economic prosperity and a vague universal humanitarianism became the only higher goods that it was morally acceptable to aim for as a society.

Such thinking indeed became popular in the academy. Before that, though, Horace Mann and his ilk were keen to use Prussian-style public education to mold Americans into worker cogs, with the molding to be carried out by progressive technocrats. Children lined up five by five to chant the Pledge of Allegiance when I was a kid. It’s only much later that relativism and social justice fundamentalism leached into the popular mind. It’s been only fifty years since these ideas caught fire in the US, with a big wave in the 1990s (PC) and a strong comeback in the 2020s (woke). That egregore is again in retreat.

But quite separately from the strands of early and late progressivism, we must remember that “casting doubt on authorities” and vilifying “collective loyalties” have always been in our DNA as Americans. The Declaration is antiauthoritarian.

Before 1776, Americans showed loyalty to royalty.

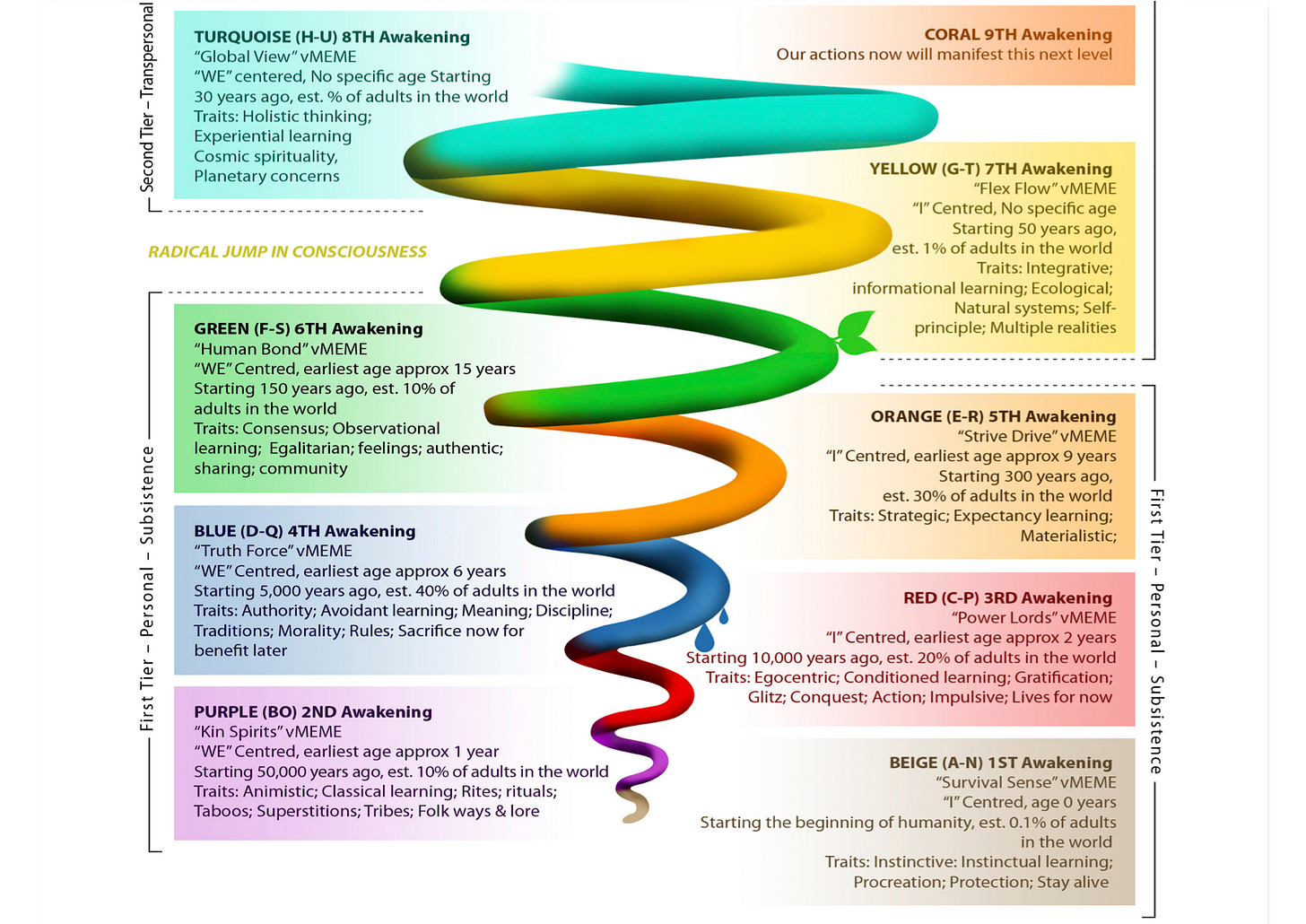

In Spiral Dynamics shorthand, we can say that Lyons objects to the rise of unhealthy Green relativism and its attendant oppressor/oppressed thinking. Still, he wants to jettison the healthy Orange of enlightenment liberalism in favor of hierarchical Blue “strong gods.” Like many first-tier thinkers, Lyons probably thinks Blue, Orange, and Green are incommensurable. But they are not. And that is why Lyons, although a Blue-whisperer, has not yet made the quantum leap.

He reminds us: We need the return of healthy Blue while preserving healthy Orange and Green—even as we drive stakes into the hearts of the specters of holy hierarchy (unhealthy Blue), technocracy (unhealthy Orange), and social justice (unhealthy Green).

I hope those who have not yet explored Spiral Dynamics’ heuristics will forgive my indulgent diversion.

As soon as I make my case for healthy Orange, Lyons comes through with a strong point about unhealthy Orange scientism.

As government joined forces with post-war psychoanalysis, this program of subtle social control solidified into the modern therapeutic state – a regime that, as Christopher Lasch noted, successfully “substituted a medical for a political idiom and relegated a broad range of controversial issues to the clinic – to ‘scientific’ study as opposed to philosophical and political debate.” This removal of the political from politics lay at the heart of the post-war project’s aims. Its central desire was to reduce politics to mere administration, to bureaucratic processes, legal judgements, expert committees, and technocratic regulation – anything but fraught contention over such weighty matters as how we ought to live, organize society, or define who “we” are.

My only quibble with the above is that political scientism was as much evolved as designed in the environment of the time. In other words, Americans, in particular, saw technocracy *win the war* and, later, *put a man on the moon.* Such achievements fueled relatively strong gods, though perhaps more hollow and ephemeral ones. Again, technocracy is unhealthy Orange, while social justice fundamentalism is unhealthy Green. Or, if you prefer, Arimanic evil and a mix of Luciferic and Sorathic evils, respectively.

Lyons is absolutely correct that both tried to drown Blue while the people were gawking at NASA missions or, later, hiding from the PC police.

Public contention over genuinely political questions was now judged to be too dangerous to permit, even – indeed especially – in a democracy, where the ever-present specter of the mob and the latent emotional power of the masses haunted post-war leaders.

In fairness, can you blame them? We can agree that muting the masses went too far, but so did the mob. Arguably, social justice can manifest as mob mentality.

But we’ve seen populism go awry time and again. A person animated by strong gods without strong guidelines is like a teenager in his parent’s car after a few strong drinks. Though, in fairness to Lyons, elite mistrust of errant public sentiment often grants authorities too much license:

They dreamed of governance via scientific management, of reducing the political sphere to the dispassionate processes of a machine – to “a social technology… whose results can be tested by social engineering,” as Popper put it. The operation of such a machine could be limited to a cadre of carefully educated “institutional technologists,” in Popper’s words, or rather to Hegel’s imagined “universal class” of impartial civil servants, able to objectively derive the best decisions for everyone through the principles of universal Reason alone.

Lyons is not wrong, as I have argued similarly here and here. His picture is of the most abhorrent Eurocrat or Deep Stater—so much so that the mental image of workers and farmers with pitchforks chasing pantsuits through Brussels and Washington isn’t all that troubling a vision.

I digress.

So what happened after all the social engineering?

The result was the construction of the managerial regimes that dominate the Western world today. These are characterized by vast, soulless administrative states of unaccountable bureaucracies, a litigious ethos of risk-avoidance and “harm-reduction,” and a technocratic elite class accustomed to social engineering and dissimulation. In such states the top priority is the careful management of public opinion through propaganda and censorship, not only in order to constrain democratic outcomes but so as to smooth over or avoid any serious discussion of contentious yet fundamentally political issues, such as migration policy.

The key question is whether the rise of the managerial regime hangs solely on the loss of amor patriae and the strong gods—and whether dismantling that regime requires their return.

Like any complex question, the answer isn’t straightforward. The suffocating plastic of social engineering was indeed stretched over the mouths of a mouth-breathing public. It is also true that the technocrats sometimes seek to quell old loves like that of God and country. In Europe, they were wildly successful. In the US, they beat the patriotic hordes back to the hinterlands and gave the city-slickers a new religion.

But the managerial regime also slowly replaced good rules with bad rulers. And this is what Lyons completely misses.

Then he jumps the shark.

Meanwhile the common people of such regimes are practically encouraged to live as distracted consumers rather than citizens, the invisible hand of the free market and the inducements of commercial and hedonistic pursuits serving not only profits but a political function of pacification.

Is Lyons trying to score a column in The New Republic or coffee with Bernie Sanders? Blaming capitalism for the world’s woes is exactly what Adorno did.

So, are we meant to lay the rise of the managerial regime at Adorno’s feet or the capitalists he hated? I suppose the anticapitalists and the capitalists could be equally responsible for the West’s lost love. Sounds fishy, though. From the left or the right, the trope lures Lyons into the notion that virtue comes from poverty and decadence follows wealth. But like any neo-Marxist or NatCon just-so story, it’s too simple. (Political economy tells a different story, as we’ll see.)

But Lyons roars:

It is preferable that the masses simply not care very much – about anything, but especially about the fate of their nation and the common good. That sort of collective consciousness, transcending self-interest and seeking higher order, was after all identified as a foreboding mark of the closed society.

And like any neo-Marxist or NatCon just-so story, this metanarrative is unfalsifiable. It’s also rife with problems.

Even if the masses cared about their nation’s “fate” and the “common good,” few can tell us just what that common good is and how we get there, and then they’ll argue to the death about it.

“Collective consciousness,” like collectivism, sounds stirring and vaguely plausible, but a collective consciousness can be a prosocial Geist or dangerous Egregore.

If F.A. Hayek is correct in distinguishing between cosmos and taxis, organizations have specific objectives, but societies are self-organizing. Hayek had seen the totalitarian horrors around him—where autocrats tried to design and plan societies—and knew society by design was a bad idea. Hayek didn’t forget that strong technocracy + strong gods = totalitarianism.

What does saying the “masses don’t care very much” mean? Surely more than that Americans have been under the spell of Twinkies and Playstations.

Political economists from Mancur Olsen to Gordon Tullock tell us that as a society becomes more complex, the incentives of the corporate and political class will unite in unholy K-street intercourse. Ordinary people will be rationally ignorant and rationally irrational about it. No amount of strong-god tonic nor national love can overcome the logic of collective action, as incentives are strong gods, too. It also takes making information more affordable and accessible (i.e., rational in the economic sense), which is exactly what Elon Musk has done with X and Vivek Ramaswamy has done with his books, such as Woke, Inc.

Without Musk and Ramaswamy helping roll back the censorship regime Lyons despises, a new “collective consciousness” might not have been possible. And, he’d better believe that Adam Smith’s invisible hand and smartphone dopamine addictions had everything to do with overcoming the various information asymmetries that gave rise to the managerial regime to start with.

In other words, culture matters. But technology and incentives matter, too.

Here, then, can we see the long historical roots of the open, neoliberal state pointed to as an ideal by Ramaswamy and Musk. Innocently or not, these libertarian-leaning businessmen’s conception of the polity is almost indistinguishable from the “post-national state” that devoutly left-wing leaders like Canada’s Justin Trudeau have set out to devolve their countries into.

Ramaswamy and Musk can ably defend their patriotism. The latter spent $15 billion to protect the First Amendment and left Canada for CA and CA for TX.

Every time I see the word neoliberalism, I chafe. My frustration originates in its lack of specificity and general usage by those on both the Left and the Right who need a bogeyman. When Milton Friedman and Hillary Clinton are both considered “neoliberals,” we have a lexical problem. But our nation’s woes, including the unfortunate rise of the managerial regime, lie in the abandonment of liberalism. And when I say liberalism, I mean freedom’s doctrine, not Clinton’s.

Unfortunately, if, like Lyons, you guzzle nationalism but have no liberalism in your worldview, you will create Boy Pharaohs.

Swedish philosopher Alexander Bard introduces the compelling archetypes of "Pillar Saints" and "Boy Pharaohs" to illustrate two fundamental imbalances in human development.

The Pillar Saint—exemplified by the OG gnostic, Plato—represents those who elevate the mind while rejecting the body, dwelling in the "Land of Ought," where ideals reign but practical action is absent. Conversely, the Boy Pharaoh, embodied by Stalin, embraces physical power and strong emotions while rejecting reflection—asserting dominance through force instead of wisdom.

These archetypes represent opposing failures of integration: sanctimony without efficacy and petulance without consideration.

Bard suggests each archetype attempts to gain power while rejecting essential aspects of human experience—the Pillar Saint abandons pathos while the Boy Pharaoh is blind to logos. Their incomplete development, coupled with aspirations to be as gods, reveals a fundamental childishness. When these immature archetypes find each other, they end up in destructive codependency. (Think Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini.)

The consequences are profound.

Pillar Saints endlessly ponder, fret, and moralize but never translate their ideals into meaningful action. Boy Pharaohs act recklessly without reflection, wielding power destructively due to their stunted capacity for thoughtful consideration—that is, “rationality,” which is strong because it tends to track the truth.

Both lack wisdom.

Lyons is playing Pillar Saint to legions of Boy Pharaohs, only drunk on strong gods’ elixer. Instead of practicing rationality, Lyons rationalizes unbounded thymos.

The “globalism” so often decried by populists is neither left nor right but the logical product of the rationalist universalism embraced by the 20th century’s post-war consensus. It is the inevitable result of treating people, and peoples, as interchangeable units in a mechanical system – that is, of regarding them without any distinguishing sense of love.

Just as globalization and globalism differ, rationalism and rationality differ. Lyons either misses this fact or wants you to conflate the two. Notice the result, though. Lyons takes us back to the cold calculus of corporation as machine to paint the managerial regime with the same tar brush. But the comparison is not quite right. (See Hayek’s cosmos and taxis again.)

God help us if the useless eaters of the managerial regime decide they love us.

But, as is increasingly obvious in our turbulent 21st century, these loveless machine-states are deeply unstable. It turns out that attempting to remove all bonds of affection from politics introduces some fundamental problems of political order. Most importantly, it has left us a leadership class essentially incapable of responsible leadership.

Perhaps we should invite all the fired bureaucrats back to USAID on the condition that they love us more than they did before.

Hold your nose because Lyons is starting to reek of Mencius Moldbug.

The noble classes of the pre-modern world’s closed societies were still capable of displaying a real sense of noblesse oblige: of having a sacred obligation to and responsibility for the people they ruled. Though modern cynics may dismiss this sentiment as a myth, it was often genuine.

Lyons goes on to lament the death of English aristocrats in WWI, which is lamentable in the sense that people dying in war is sad. Lyons is worried about the aristocracy.

By contrast, because we care about more than strong gods and patriotism, I worry about the decline of Jefferson’s natural aristocracy in America, that is, people with virtues and talents being tamped down as they have been in Europe. Our spirits of creativity, entrepreneurship, and innovation are strong gods, too, of a different pantheon.

Today our elites no longer betray any similar sense of special obligation to their people. But then we can hardly expect them to, given that all the strong bonds of loyalty that once tied them to their countrymen, transcending divides of wealth, education, and class, have been severed. They conceive of themselves as meritocrats, of no special birth and therefore no special responsibility.

Special birth? Oh my. Real patriots would call N.S. Lyons a Tory. We are Americans—or were once. We don’t need formal aristocracy to preserve the strong bonds of loyalty. More than any other people, Americans are barn raisers.

More importantly, they have been taught from birth that they ought not even conceive of their nation as particularly their own or to love it any more than any other portion of humanity; their self-conceived domain is one without borders, the global empire of the open society.

This is the Eurocrat’s vision. And, in Europe, it has taken hold.

America, having come out of WWII the victor, was never entirely on board with that vision. Our cosmopolitan aristocrats were. Indeed, the managerial regime is our aristocracy. Still, even the vast and unaccountable Blob doesn’t care much for the UN, and it has used NATO, the Five Eyes, and the EU as tentacles for its technocratic imperialism.

Then Lyons asks: “Whom does government serve?”

This is perhaps the most pressing question of politics. In theory the leadership class that rules us is supposed to represent and govern on behalf of the common people and their best interests. This is meant to be precisely what distinguishes our regimes from tyranny, “tyranny” in the classical lexicon meaning rule for private gain rather than for the common good.

Lyons forgets that governments are just protection rackets dressed up in royal finery. After making us an offer we can’t refuse, they should love us harder. Let’s pass over Lyons’s curious definition of tyranny and stipulate it’s partially correct.

But no one can truly represent or act rightly for the wellbeing of another if they bear no particular concern for them. It is love, and only love, that can really guarantee that anyone acts in the best interest of another when they could do otherwise. Love is the only force capable of genuinely liberating us from selfishness.

How does one operationalize “the only force capable of…liberating us from selfishness”? X loves America, so vote for X if you love America, too? That’s just politics as usual.

What if, instead, we all practiced loving first ourselves, then our families, then our communities, and so on…. in a kind of Yankee tikkun olam. If everybody practiced loving and showing love in ever-expanding radiative self-sovereignty, we wouldn’t need to try to project love onto something so loathsome as politics.

Love in politics is like compassion in crime.

It is a modern conceit that those with power are kept restrained, uncorrupted, and ordered to justice and the common good primarily by lifeless structural guardrails, by the abstract checks and balances of constitutions and laws. The ancients would have maintained that it is far more important that a king be virtuous, and that he love his people. And is this not plausible?

It is the premodern conceit that those with power would or could consistently be virtuous. We need only look at bloody premodern history to see enough war and torture of dissidents. Lord Acton was right about absolute power. Lyons would do well to go back and read Tolkien or Plato’s account of Gyges’s ring. Abstract checks and balances of constitutions and impartial laws might not be enough. But they have helped mute the aspirations of those who would act with impunity—especially relative to the Moldbuggian past Lyons so admires.

Fundamentally, a father doesn’t treat his children well, refraining from abusing or neglecting them and raising them rightly, just because he obediently follows the law or some correct set of rules and standard operating procedures. He does so because he loves his family, and from that love flows automatically a spontaneous ordering of all his intentions toward their good. He would do so even in the absence of externally imposed rules. Love is an invisible hand all its own.

I think I’m going to need a Zofran.

It is this invisible hand, not that of the market, that is so glaringly absent from the heart of our nations. If ours seems a cold and callous age in general, our ruling class characterized by its indifference and our societies by division, dissolution, and despair, surely this lack is the real cause.

Why this legerdemain? Lyons purposefully conflates market process and rule of law (unplanned order) with the managerial regime and rule of technocrats (planned order)—all while shitting on the Constitution, imperfect as it is. It’s bizarrely analogous to lumping Adorno with Popper. And it ain’t right.

The enlightened man, the conservative Russell Kirk once observed, “does not believe that the end or aim of life is competition; or success…” Nor does he hold any foolish political “intention of converting this human society of ours into an efficient machine for efficient machine-operators, dominated by master mechanics.” What he recognizes instead is that “the object of life is Love.” And so he knows, what’s more, “that the just and ordered society is that in which Love governs us, so far as Love ever can reign in this world of sorrows; and he knows that the anarchical or the tyrannical society is that in which Love lies corrupt.”

Never mind that no one has ever accused the managerial regime of being efficient. To Russell Kirk, I offer the words of the great Gordon Sumner: “If You Love Somebody Set Them Free.”

Our betters can treat us like children to be coddled and punished or, as adults with wings, to be pushed gently from the nest of nanny statism and paternalism. In our freedom and adulthood, we will experiment and self-organize in love. We will make mistakes along the way, but these will not be the catastrophic systemwide errors made by even the most loving sovereign. These will be the local learnings of a free people building a City on a Hill.

Together, we can fashion a community within the simple protocols of a free national order. Love will be the happy byproduct of proximate people dedicated to serving each other in markets, mutual aid, and good old-fashioned neighborliness. Love cannot be outsourced to Washington. Nor can it be rained down upon us like federal largesse.

That’s because nations don’t love. People do.

Lyons complaining that the "masses don't care very much" is somewhat strange, considering one of the supposed benefits of Neo-Carmalist monarchy is that the masses aren't supposed to care, they can outsource the caring to the Aristocrats.

“Political economists from Mancur Olsen to Gordon Tullock tell us that as a society becomes more complex—the incentives of the corporate and political class are to unite in unholy K-street intercourse.”

I think a comma would be better.